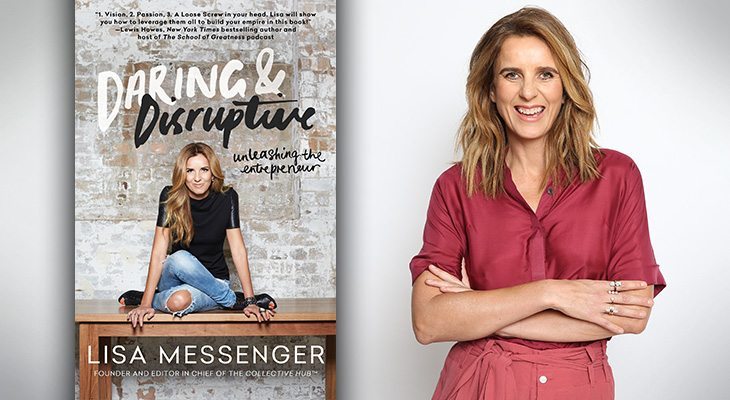

The following excerpt was selected exclusively for StartupNation readers from “Daring & Disruptive” by Lisa Messenger. Excerpted with permission by North Star Way publishing, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

I think the key to failure is that if you’re going to fail, you may as well do it fast. I have seen so many people do it ridiculously slowly and painfully. It kills me every time to watch someone experience great personal and professional grief over many months or even years. I’ve never really failed slowly, probably because I’m too impatient for that.

If I’m going to fail, then I want to do it well—fast and with minimum risk. And as a result of this ethos, I’m quite prepared to try out a lot of new and interesting things, unafraid of the outcome. The traditional mind-set is to write a laborious business plan to perfection, run a zillion focus groups, do all your market research, and check every conceivable box before launching into something, but I rarely (okay, never . . . yet) do that.

To take that approach requires a huge investment of time, resources, and money, and you are already deep into the project’s life cycle before you even know if someone is going to buy what you’re selling. And by the time you launch, you’ve perfected your idea to within an inch of its life, so when the market gives you feedback, it’s often too late to change, move, and adapt. Instead, the experience can leave you feeling paralyzed by disappointment and with a sense of hopelessness about pursuing other ideas.

Related: 5 Things Entrepreneurs Need to Build a Career Plan

Don’t get me wrong—I do my due diligence, but just not to the point that the poor project is suffocated or strangled before we even begin.

Of course, that’s not to say I take every idea I have and pursue it with reckless abandon! It’s no stretch to say that entrepreneurs will come up with a hundred or more business ideas in a year; that’s less than two decent ideas a week, which seems more than fair. The ideas are not always viable, but they’re always showing up. They come from listening and watching everywhere you go, and being open to the opportunities that you find along the way And they can stem from your own needs or from observing markets around you.

I tend to sit on a new idea and examine it in my head. I try to gauge my level of interest and overall passion, asking myself if I have the sweat and tears to pour into it, because I know that’s what will be needed should I decide to do this. In other words, you need to be really juiced up and passionate about it, or it will never fly.

If I feel the idea has wings, I generally write up a few pages on it—literally back-of-the-envelope stuff, things such as an overview, indicative model, potential markets, and indicative marketing/ launch, so that I have something to test out with potential partners.

It can happen within an hour to a week of the birth of the idea, and if I get a bite, I investigate further and start to make more concrete plans. But if I discover that no one is interested, then I bop it on the head, moving on to something else. Pretty simple, really. I do this over and over and over again. It is the only way I work. I never plan more than this initially. And as it grows, you can look at extension ideas and test them out in the same way.

Related: Sign up to receive the StartupNation newsletter!

“Daring & Disruptive” is available now wherever books are sold.