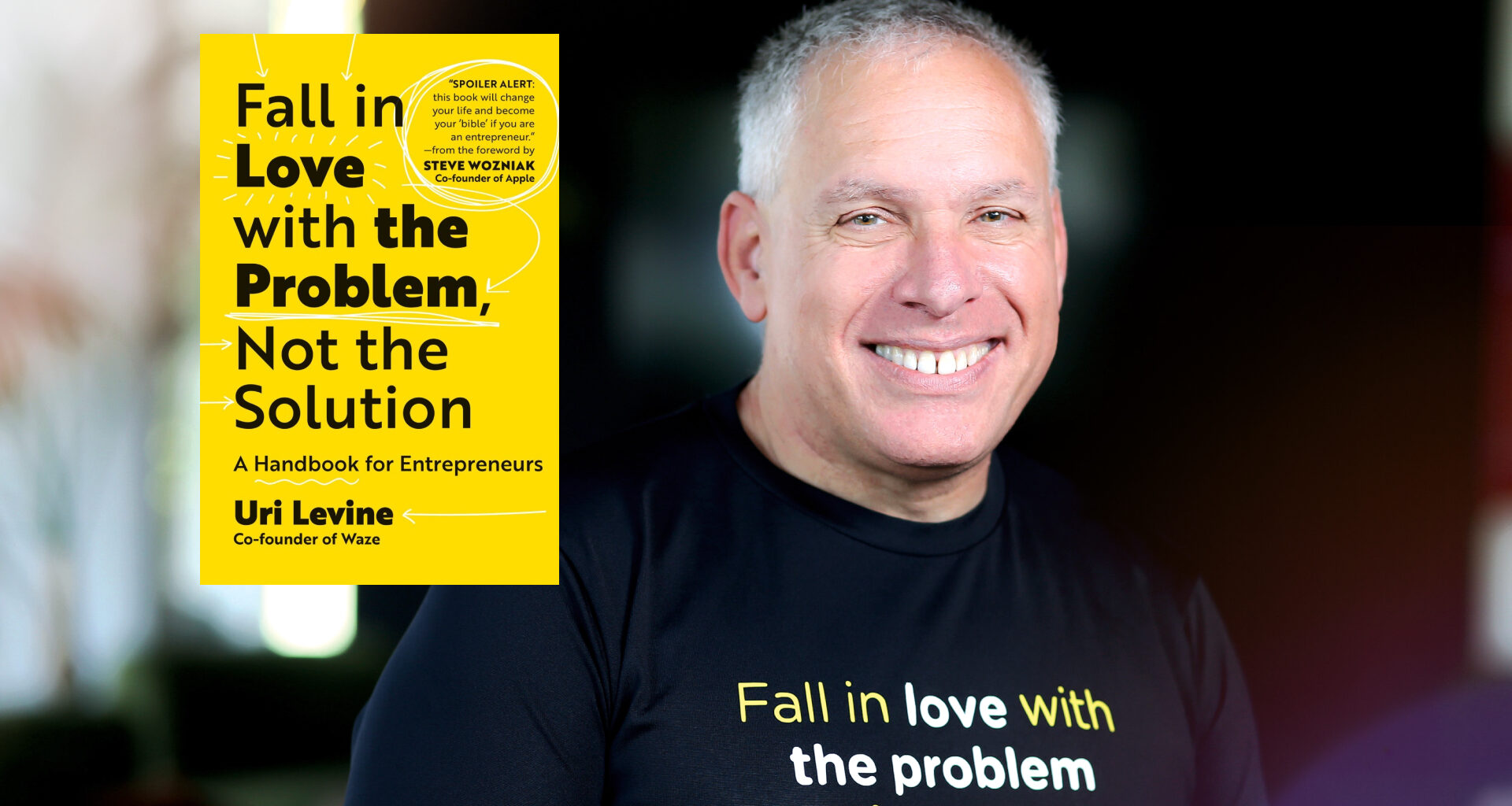

The following is an excerpt from “Fall in Love with the Problem, Not the Solution“ copyright © 2023 by Uri Levine. Reprinted with permission from Matt Holt Books, an imprint of BenBella Books, Inc. All rights reserved

A START-UP IS LIKE FALLING IN LOVE

Building a start-up is very much like falling in love. In the beginning, there are many ideas you could pursue. Eventually, you pick one and say, “This is the idea I’m going to work on,” much like you might go on many dates until you eventually find someone and say to yourself that this person is “the one.”

At the beginning, you spend time only with that idea. This is when you think of the problem, the users, the solution, the business model—everything. Just like you only want to spend time with your new loved one as you begin falling in love.

When you finally feel confident enough, you start telling your friends about your idea, and they usually tell you, “That will never work,” or “That is the stupidest idea I’ve ever heard.”

I’ve heard that many times. I think that people don’t say that to me so much anymore, but in the beginning, they used to say it a lot. Sometimes you take your date to meet your friends for the first time and they say, “That person is not for you.”

Solve the REAL Problem … Not the Symptom

This is usually when you disengage from your friends because you are in love with that idea, you are in love with what you’re doing, and you don’t want to listen to anyone else.

The good news is that you are in love, and you don’t listen to them.

The bad news is that you are in love, and you don’t listen to them.

But this is the reality, and it’s relevant for many aspects of your life. If you don’t love what you’re doing, do yourself a favor and instead do something you do love, because otherwise, you’ll sentence yourself to suffering.

You should be happy!

It can be detrimental to ignore what others are telling you. Maybe your friends, potential business partners, or investors had something important to say and you didn’t listen! But, at the same time, you must be in love to go on this journey. It will be a long, complex, and difficult roller-coaster ride. If you’re not in love, it will be too hard for you.

Before we founded Waze, I had been working as a consultant for several start-ups. One of them was a local mobile navigation company, Telmap, that built navigation software for mobile phones and was offered as a service to mobile operators, which then offered it as a paid subscription service to their subscribers. It was essentially a B2B2C (business-to-business-to-consumer) company. Telmap licensed its maps from third parties such as the Israeli company Mapa and international mapping giant Navteq. Telmap didn’t have traffic information, though.

I approached the CEO and shared my thoughts. The Telmap platform seemed an ideal one to carry out my vision.

“No one cares about traffic information,” the CEO said, rebuffing what I thought was a brilliant idea. “They care about navigation. I don’t think traffic information will be actionable.”

By “actionable” he meant “we’ll never be able to get people to use it enough to make it worth our while financially or to change their route accordingly.”

Back then, the only way traffic information was used was with color-coding applied to the map—green meant there was no traffic, yellow meant there was traffic, and red meant the traffic was heavy. But that information was not particularly helpful. On busy roads and intersections, there is traffic every day between 8 am and 9 am and between 4 pm and 6 pm, and on the same road at midnight, there is no traffic!

I was persistent, though. Anyone who knows me is aware that once I get an idea in my mind, it’s nearly impossible to dissuade me from pursuing it. Telmap had 50,000 users at the time, all in Israel, and all using their mobile phones with GPS. I built a theoretical statistical model to show how those 50,000 random drivers would be enough to create actionable traffic information. It was a very simple model that turned out to be accurate later when we built Waze.

Here’s how the math works: 50,000 users out of about 2.5 million vehicles in Israel (the number of cars and trucks on the roads at the time) was some 2 percent of the total. On a highway during busy hours, there are between 1,500 to 2,000 vehicles per lane, so 2 percent of that is a 30-to-40-vehicle sample per lane.

Now, if a highway is three lanes across, that would be about 90 to 120 vehicles per minute. If we could gather location and speed at all times, this would be a large enough sample to know what the traffic is like on that road. I tried again to convince the CEO, but obviously I didn’t make the claim strong enough to convince him.

While I stopped trying to convince him, I nevertheless carried the urge to work on this project for a while until, around a year later (it always takes longer than you would think), as a result of my background and my reputation as an advisor to start-ups, I was introduced by a mutual colleague to two entrepreneurs, Ehud Shabtai and Amir Shinar.

Ehud and Amir were working together at a software house that Amir was running. Ehud was the Chief Technology Officer (CTO), but in his “night job” he had built a product called FreeMap Israel.

The FreeMap Israel app was a combination of two parts—navigation and map creation. The app created the map as you drove and used it at the same time for navigation. It ran on personal digital assistants (PDAs), as there were no iPhones yet. As its name implies, FreeMap Israel was entirely free—both the app and the map.

Ehud had a problem that was similar to mine: He needed maps for his app to work, but it was too expensive to license them from a third party. This was a critical issue for both our visions because without maps it would be impossible to build a critical mass of users that would generate actionable traffic information. But a start-up couldn’t afford the high prices the mapmaking companies were charging at the time.

Meeting Ehud and Amir was my second magical moment; it was when I knew I had found what I needed to complete my vision of an everyday “avoid traffic jams” app. I had an idea but no way to implement it. Ehud had the conceptual and technological answer for the cost of the map and a similar vision. In fact, Ehud was already multiple steps ahead of me. Mine was in theory; he had actually already built a lot of what was needed. The magic of Ehud’s self-drawing maps that created a “free” map was a prerequisite for developing a free application that would encourage use by the number of users who were needed in order to generate accurate traffic data.

From the beginning of Waze, after we joined forces in 2007, it was clear that a GPS-powered mapping/driving/traffic app was exactly what we were going to build. We certainly realized that smartphones with operating systems (and therefore the ability to run apps) and built-in GPS chipsets were becoming more and more popular. What we didn’t know back then was that Apple would revolutionize the business when it launched the App Store in 2008. That would in turn give Waze its biggest push. There was even more magic in that the same app that gathers the data also uses it at the same time—it’s the crowdsourcing of everything!

IDENTIFY A BIG PROBLEM—ONE THAT’S WORTH SOLVING

Start by thinking of a problem—a BIG problem—something that is worth solving, a problem that, if solved, will make the world a better place. Then ask yourself, who has this problem? Now, if the answer is just you, don’t even bother. It is not worth it. If you are the only person on the planet with this issue, it would be better to consult a shrink. It would be much cheaper (and probably faster) than building a start-up.

If many people have this problem, however, then go and speak to them to understand their perception of the problem. Only afterwards, build the solution. If you follow this path, and your solution eventually works, you will be creating value, which is the essence of your journey. If you start with the solution, however, you might be building something that no one cares about, and that is frustrating when you’ve invested so much effort, time, and money. In fact, most start-ups will die because they were unable to figure out product-market fit, which in many cases happens when focusing on the solution rather than the problem.

There are many reasons to start with the problem, in addition to increasing the likelihood of creating value. Another key reason: your story will be much simpler and more engaging; people understand the frustration and can connect to that.

Companies that fall in love with the problem ask themselves every day: Are we making progress toward eliminating this problem? They tell a story of “This is the problem we solve,” or, even better, they narrow it down to “We help XYZ people to avoid ABC problems,” whereas for companies that focus on the solution, their story will start with “our system . . .” or “we.” If the focus is about you, it will be much harder to become relevant. If the story is about your users and a focus on the problem, it will be much easier to gain relevance.