Welcome to another special show in our “Problem Solvers” series, focusing on startups that were spun out of universities and national research laboratories that have the potential to change the world.

Today’s show features PsiKick, a company that has combined research from the University of Michigan and the University of Virginia to make the Internet of Things possible. What is The Internet of Things, you ask? In no uncertain terms, it’s the future. We take a shot at explaining exactly what the Internet of Things is, how it will impact you and how the folks at PsiKick are going after their piece of this $300 billion near-term opportunity.

The first Internet “thing” was an appliance—a soda vending machine at Carnegie Melon University. The programmers at Carnegie Melon could connect to the machine over the Internet, check the status of the machine and determine whether or not the soda bottles were being chilled.

To be more specific, “a thing,” in the Internet of Things, can be a heart monitor implant, livestock with a biochip transponder, a car with a built-in sensor to sense tire pressure, or any other natural or man-made object that can transfer data over a network.

And this Internet of Things is growing. Forecasters conservatively predict that more than 20 billion Internet of Things devices will exist within a few years, creating more than $300 billion in opportunities for businesses by 2020.

In order for these “things” to connect and share information, they must be powered by something. Billions of batteries constantly needing replacement does not bode well, which is one limiting factor in the Internet of Things.

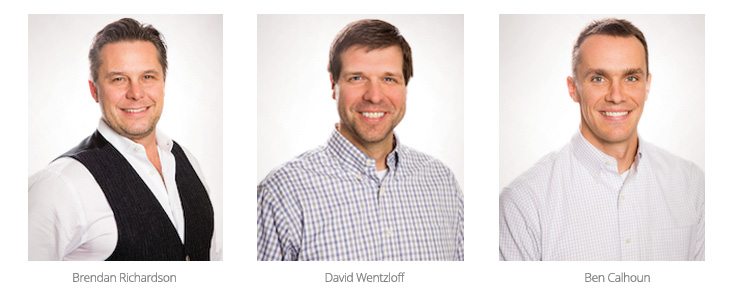

Enter our guests, true Problem Solvers. University of Michigan professor David Wentzloff is the co-CTO and cofounder of PsiKick, along with his colleague, professor Ben Calhoun at University of Virginia. They linked up with PsiKick founding CEO Brendan Richardson to set the vision and marshal the resources (including the venture capital) to create the company, which now employs 31 people in three offices (Ann Arbor, Charlottesville and Santa Clara).

PsiKick is on its way to becoming a super startup that will enable the rapid expansion of the Internet of Things by commercializing chips that require 1/1000th the amount of power that current computer chips consume. The chips require so little power that instead of hard wiring or conventional batteries, they can be instead be powered by the environment.

Key takeaways from this show include:

- Do your research: What you don’t know can and will hurt you, so get as smart as you can with the information that is available to you. Don’t leave big questions unanswered. Remove as many of the unknowns as you can.

- Surround yourself with smart people: Always play to your strengths and be honest with yourself about your weaknesses. Allow others to fill those seats instead.

- Exploit your network of contacts: Starting up is not the moment to be shy with your Rolodex. Reach out and tap into your network for advice and introductions. As in the case of PsiKick, it could result in being introduced to your future CEO, a clear path for your startup and millions in funding.

- Create a demonstrable case: If you have a business idea that people may react to with doubt, do everything realistically possible to demonstrate that your idea works. In PsiKick’s case, that meant having a functioning microchip that functioned well and consumed far less power. This converted a skeptic into a passionate advocate and got their founding CEO on board.

- Be one with your motives: Don’t be casual about the “why” of what you’re doing. Sure, the profit motive is crucial. That makes the capitalistic world go round. But beyond money, PsiKick founders also wanted to see people’s lives improve through the impact of their innovation. This was a huge motivator, adding significant meaning and the will to persevere in their challenging work.

- Know when to get out of the way: Businesses evolve and morph over time. Needs change. Don’t get attached to your current role if that might get in the way of seizing on opportunity. In PsiKick’s case, the founding CEO replaced himself with an industry titan CEO that is well-suited to take the company to the next level.

We loved the path we heard Dave and Brendan describe for their university spin-out, PsiKick. It’s these kinds of innovators and these kinds of startup companies that are going after BIG problems. By coming up with extraordinary solutions, companies like PsiKick are perfect for our “Problem Solvers” series.

Stay tuned for a future StartupNation Radio show to learn of PsiKick’s progress.

JEFF: It is indeed time for StartupNation Radio and (on) today’s show, we’re going to do another problem solvers series. We’ve got the Sloan brothers back on StartupNation Radio. Rich, what do we got for us today?

RICH: Well, this is a problem solver show. The universities across this country are solving big problems. Today we’re talking about the internet of things. You may have heard about that lately?

JEFF: I have.

RICH: We’ve got some major problem solvers addressing a global opportunity.

JEFF: Right, now big stuff, now entrepreneurs out there thinking about starting a business of your own. You don’t have to be thinking like big universities and doing the internet of things, you can still be doing whatever it is that you want to do, the idea is to learn from how they’re doing it and apply those nuggets of wisdom to what you’re doing and what your dreams are. And we’re going to help you make those dreams come true on this edition of StartupNation Radio. Stick with us, great show ahead.

JEFF: Okay, it’s time for another great edition of StartupNation Radio. We’ve got another special show. It’s in the problem solver series focusing on startups that were spun out at universities or have been spun out at universities and national research laboratories and that are literally changing the world. These are big, big ideas, big problems being addressed, big ideas as the solutions. Rich, it’s amazing stuff that’s happening.

RICH: It is, it is, and so this is happening at universities across the country. This is happening at national labs and what happens is you’ve got this extraordinary, genius, ultra capable people who are in the labs working—thinking big, thinking differently and having those epiphanies that truly can and are changing the world. And so today, we’re featuring a company on StartupNation Radio, this problem solver series, that results from a combined research effort of two universities.

JEFF: Yup, yup, and what we’re featuring today is the subject matter of something we call the internet of things. There’s lots of big trends going on out there in the business world and the world of venture capital and the world of business startups etcetera. And so this internet of things thing—right, right? Has become one of those really big, massive, important trends and it’s going to affect our everyday lives. I mean this is going to filter into our lives and really impact everything we’re doing. And we’re going to find out how it’s going to impact us; in fact it’s projected to be a two, three hundred billion dollar opportunity. This is big stuff.

RICH: It is, and our guests today come out of the University of Michigan and University of Virginia, so this technology, like our themes for these shows, come out of these labs and is set to change the game, globally.

JEFF: Let me say one thing. On the subject of this big things happening, of course we got a lot of small, relatively speaking, smaller dreams out there being pursued by great entrepreneurs and one might ask you know, I listen to StartupNation Radio because I want to learn about how to make my business dreams come true. So listen, I want to make sure as we go through the show and I know we’re going to do this for or listeners, our loyal listening audience, we want to make sure we also pull out some of the nuggets that these big thinkers are deploying as they pursue their dreams and goals and break it down and make it relevant to you know, maybe the average entrepreneur out there who is starting a business that may not have such a global impact but certainly have a huge impact on their own personal lives.

RICH: You know what Jeff, I think the table is set to share those kinds of lessons and takeaways because we’ve—our guests today have gone through business startup challenges that almost any startup has to face. But it’s in the context of this fascinating thing called the internet of things.

So Jeff, I want to start off by saying, do you have any idea when the internet began? Guess the year.

JEFF: Uh oh. I can tell you I guess when it became relevant, probably the early 90s, late 80s, when people actually had the hardware to make the connection.

RICH: Don’t think it through too much. Give me a date.

JEFF: Defense project, probably the 60s when it originally began.

RICH: You gave the defense research a lot of credit.

JEFF: 61.

RICH: It’s actually 1983. Let me just Google that. When was the internet created—in preparation for today’s show I was researching this last night and the answer to that question is, ARPANET is what it was originally called. To your point, it was done by the defense—out of that group. 1983, and then, to get to a later date, in 1990, there was something called the World Wide Web.

JEFF: That’s the old www we still use today.

RICH: Now, when we talk about that 1983 thing, the reason I wanted to call that to your attention was because that was when the internet of us started to become possible and it led to everything we know today, how we operate in this world. But the internet of things actually started very shortly after that and again it happened at a university, it was some Carnegie Mellon researchers and they actually set up a demonstration of talking to a machine, a thing for the first time and it was a Coke vending machine down the hall. So that was the first thing that got onto the internet. So the legend goes, anyway.

Now, of course Coca-Cola is very important to research and to progress, right, at universities.

JEFF: Sugar and caffeine, the basis of a lot of great research.

RICH: How many great business ideas did you and I create with a good cold Coca-Cola and a pizza? That was the beginning. But now where is this going? You’ve got an unbelievable array of applications, billions of devices are going to be hooked up to the internet of things. Some say 20 billion devices by the year 2020. These are things like cars, live stock with biochip sensors. It could be heart monitor implant. These are just examples of the kinds of things that can be connected as an internet of things and they don’t require any kind of human interface or human to human involvement, it’s just things talking to things and sharing information.

So that really in a nutshell is the internet of things.

JEFF: Amazing. I guess the question for me is breaking it down and making it practical. You’ve got this great technology hookup going on, how do we break—who is going to be the pioneers that actually turn it into a business opportunity?

RICH: Well, here’s the thing Jeff. This gets to the startup we’re going to talk about on today’s show. We talk about startup in the context of a business that has been created and is on a trajectory for growth. So you’ve got a problem standing in the way of the internet of things. Think of the hackers in Russia. When you get all those devices connected to the internet, they’re going to be all over that, that’s really scary. But there’s another huge problem, which is these things require power in order to be talking to each other.

How are we going to have billions of batteries that have to be changed out every now and then? That’s just not practical. So the innovators we’re talking to today has addressed this issue of the power required for the internet of things and they’ve created an ultra low power chip, essentially, one one-thousandth of the power required for a normal chip in order to be online and be part of this internet of things.

This opens up a world of possibilities to make the internet of things happen.

JEFF: Okay, so we’re going to hear about that today on this edition of StartupNation Radio. We’re going to hear all these guys making this happen and making a practical, breaking it down, creating business opportunity out of this and how they’re doing that. Today’s edition of StartupNation Radio is brought to you buy Comerica Bank, we’re proud to have them as a sponsor. Stick with us, we’re going to learn how they and maybe you can get inspired to take advantage of the internet of things. Stick with us on StartupNation Radio.

JEFF: Okay, welcome back to StartupNation Radio, brought to you by Comerica Bank. We’ve got the Sloan Brothers in studio, and we’ve got an amazing guest on the line, we’ve been talking about the internet of things Rich, big problems being solved, big business opportunities resulting.

RICH: That’s right. So the internet of things is the connection of all these devices, whatever it may be. There are people who are doing fundamental research to solve the problems and overcome the hurdles that are getting in the way of this proliferation to billions and billions of devices that come online and change our world, hopefully very much for the better. One of the researchers that is at the core of the internet of things is a professor at the University of Michigan by the name of David Wentzloff. And we are bringing Dave onto our show today to talk about his research in this field and so Dave, welcome to StartupNation Radio.

DAVE: Thanks Rich. It’s good to be here.

RICH: So we’re reaching you in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Now are we reaching you in your university base digs or are you sitting in an office at a startup company?

DAVE: Sitting in an office at a startup company today.

JEFF: Can I jump in really quickly? I think it’s important to understand how you go from working in a research laboratory to sitting in an office of a startup company.

RICH: Let’s do that. So a typical professor, we picture by the way not just teaching but doing this kind of research, often times with funding grants and things of that kind but where did this start for you Dave?

DAVE: Sure, this started for me back when I was a PhD student myself at MIT and got interested in low power circuits and low power wireless communications in general, and that’s around the time I met one of my long time now collaborators, Ben Calhoun. We were both speaking together at MIT and the two of us both graduated around 2007 and became professors at our respective… then went back to University of Virginia, myself back to Michigan. Then worked on low power digital circuits, I work on low power radios and those two things dubtail quite nicely to form very low power and ultimately battery less complete systems with wireless communication and sensing interfaces and the ability to process basically everything you’d think of in an internet of things device.

RICH: Okay, Jeff, this is interesting in and of itself. Let me stop you there. So Dave had a collaborator, a colleague who had some very complimentary capabilities here. As you and I have experienced in business, one of the things that he had the opportunity to do was create a lot of really cool, creative energy by bouncing ideas back and forth with this colleague. Is that fair to say, Dave? Was that significant in your evolution?

JEFF: That is interesting. I want to ask, was it the bouncing ideas off of each other and collaborating relative to the big R, research, or was it you know, were you guys starting to say, hm, this could be a business opportunity as well.

DAVE: I would say it started as a research question. The question we ask was ultimately, what could you power with an average power budget of 10 microwatts. Let me just give you a little bit of content with that. This ties back to powering, how do you power tens of hundreds of billions of devices from batteries. Well, if you want those devices to survive indefinitely off harvested energy sources such as solar power, maybe indoor light for example, or potentially RF powers by something that you transmit from a nearby router like a Wi-Fi router, for example. When those devices have to have average power consumptions on the order of ten to twenty microwatts and make that practical.

JEFF: And since our listeners don’t know what a microwatt is, we’re just talking about tiny amounts of power consumption.

DAVE: Tiny amounts of power. So let me put that in context, you know, so a cell phone, when a cell phone is on and communicating, let’s say for a phone call, you might be consuming anywhere from 500 milliwatts—so half a watt, to make a watt, especially if you’re using the display at the same time. Now, we’re talking about ten microwatts, which is about 100,000 times lower power than your cell phone. So that’s a dramatic reduction in power consumption, but that’s what’s required to run a device continuously off something like indoor light. So we ask the question what can we do in that power budget and that was how we got started on this entire path.

RICH: Very cool. This is very cool, fascinating. In talking with Dave, he was sharing with me, the power required being so low, he’s developed essentially a band aid type of—what would you call it, sensor, that you apply to the human skin and it actually, because of the temperature differential of the skin versus the ambient environment, that temperature differential creates a current that powers a sensor that acts as an EKG that then transmits that information. These are the kinds of fascinating things Dave is able to do with these technologies.

JEFF: Dave, I have to ask you. At that point early on, you guys were collaborating to achieve a research objective. Let me just probe on that a little further. What drives a guy like you in a position that you’re in—what’s the outcome, what’s the reward? It’s a little bit of a leading question, but you know what’s the outcome of the research? At this point you’ve indicated you haven’t thought of let’s say profit motive yet. What’s driving you at this point?

DAVE: Yeah, I think it’s a curiosity—that’s a great question. I think it’s a curiosity. It’s a desire to do something very interesting and different and challenging and you know, it’s something that we—in all of our research projects in the universities, something we’re always looking to do which is you know, try and accomplish something that might seem like science fiction or might seem impossible at the time but maybe isn’t necessarily violating any laws of physics, at least not directly. So you set goals like that, very ambitious goals, ambitious targets. Out of that, innovation is almost required. It’s necessary in order to accomplish those goals.

Usually, good things come out of it on the back end.

JEFF: Yeah. For someone out there who is listening who is not in a research environment but instead may be pursuing a hobby or going about their everyday life whatever it may be, they’ve got a passion for something and really they’re doing what they’re doing and diving deeper and pursuing their passion in an insane way because they’re passionate about their thing.

RICH: Yeah Jeff, when I make a great tasting soup I’m not thinking of selling it but it could lead to a recipe that’s phenomenal.

JEFF: But, at some point whether you’re a researcher, whether it’s a guy making soup, the light bulb goes off and you say, and it’s driven by a variety of things in the case of researchers that may be driven by, I want to keep doing my research. In order to do that, I need to ultimately fund that research somehow, or it may be, hey this is America, nothing wrong with starting a business emanating from this great research and profiting from it.

Dave, what was the moment of metamorphosis for you where it went from strictly a research focus to a business focus?

DAVE: I’d say the motivation for that, I would just throw in there, beyond starting a business for profit, it’s just to make an impact, you know, from inside the university, it becomes very difficult to make such a dramatic impact rather than spinning at a company and actually developing these devices, commercializing and selling them, you can have much broader reach. I say that’s a third motivation, just throw in there.

As far as for us, I remember this very clearly, February 2012, Ben and I were at a conference out in San Francisco and we decided to take a day trip out to Half Moon Bay and we’re walking out on the water, low tide and walking out on the water and discussing—

RICH: And the heavens open up.

JEFF: I was going to make it—I bet a lot of creative stuff happens at Half Moon Bay. Anyway, yeah, in your case I want to hear about this. So what happened?

DAVE: We certainly got a lot of interest and, from potential investors and just former colleagues of ours who had seen the types of things we were doing and started planting seeds, you guys should really think about spinning this out. For us it was a combination of push and pull. That was the pull, the push side, both of us were very near to achieving tenure at the universities and after tenure you get a year of sabbatical and so the timing for us was also perfect to invest some time and spin the technology out.

RICH: Okay, so that Jeff, was the moment they started to turn the quarter. And what we’re going to talk about when we come back from the break is we’re going to talk about the critical next step for them which was identifying a business leader for this company and we’ll talk about how to play to your strength, how to fill in for your weaknesses and bring in expertise into a company so that you have a well rounded team in order to go execute on your opportunity. When we go back from our break, this is our problem solver series here on StartupNation Radio. Coming back shortly.

JEFF: Alright, welcome back to StartupNation Radio. Big problems, big solutions, big opportunities Rich, on today’s show.

RICH: That’s right, we’re talking about the internet of things and we’re speaking with professor David Wentzloff at the University of Michigan who is not just a professor at the university with his extraordinary work of ultra low power chips and sensors and whatnot but the fact that he spun out a company and it is something we’re going to be introducing.

JEFF: That’s what I want to learn more about. Of course this is StartupNation Radio so all researchers are really, really cool. By the way, you and I both have a fascination with science and technology and—yeah, sickness, love it.

RICH: A condition.

JEFF: We probably share that with Dave. He’s probably got it on steroids obviously, that’s his life, which is great. Without people like that, we wouldn’t have the great innovations that we do and people that pursue these things are those that do solve these big problems. That is the theme of today’s show. So we’re learning about—in the last segment, we finished up by talking about that transformation moment where we went from pure research, being pursued—

RICH: To the I want to start a business.

JEFF: Starting a business. And of course being StartupNation Radio, we’re going to focus on that. Before we get to that, folks out there listening, I want to make sure that you understand. You can go to StartupNation.com and click on radio to find all of the websites and contact information relating to today’s guest. You can do that with every show. You’ll also find there transcripts of this show, of all the shows, our personal show notes and additional insights, etc, etc, and you can also post questions there, we’ll get them answered. Check that all out at the radio page, StartupNation.com. A good opportunity to continue the conversation, probe further, learn more, etc.

RICH: So professor Wentzloff. You were sharing with us just before the break that you and your colleague, Ben Calhoun, out of the University of Virginia while you at that time and were remain today a professor at the University of Michigan. You said, we want to start a company so we can create these ultra low power sensors and chips and devices for the internet of things. At that point, though, what’s your next move? Because you guys haven’t ever run a business like that.

DAVE: That’s right. Yep. Fair point and you know, our main—I mean the way we approach anything, whether it’s research or starting a business, speaking of both Ben and myself, is—to surround ourselves with smart people, ask, identify where we don’t have the expertise, find people who do or ask lots of questions, and basically get smart about you know areas where we need to maybe brush up on—for example, starting a business. How do you take technology, what’s inside a university, and spin it out. Luckily we have known, we have several friends or former colleagues from MIT who had done something similar. That was the first place we started, was talking to them.

RICH: Very good. in that process, one of the things you shared with us that became clear to you were you were going to need a leader for this company who had been there, who had done it, who could bring with him the savvy and wisdom to run a company that—of this variety.

JEFF: And run a company, obviously that’s from an operational standpoint, but also have the vision and the knowhow.

RICH: That’s a good point, lead is a better word.

JEFF: Vision, and pursue that vision, and obviously maintain the day-to-day operations as well.

RICH: Okay, so with that, we actually want to bring up our next guest on StartupNation Radio and his name is Brendan Richardson. And Dave, Brendan is the guy you identified as the leader for this enterprise. So Brendan, welcome to StartupNation Radio.

BRENDAN: Thanks guys. Good to be here.

RICH: Brendan, how is it you came across to Dave and his partner Ben?

BRENDAN: I met Ben and Dave through a mutual friend of Ben’s, entrepreneur friend of Ben’s that had heard that they were looking for somebody to help spin this technology out and so I agreed to meet with them and hear about it because I knew a little bit about semiconductors but I didn’t fully understand what they were trying to do when we first got connected.

JEFF: Let me first say this Brendan. It’s a big gulp to get into the microprocessor industry, right? I mean that is ultra competitive, lots of barriers to entry, you know about this space, right, you have a background in venture capital, you’re a serial entrepreneur.

BRENDAN: I wasn’t a serial entrepreneur at that point. I classified myself as a recovering venture capitalist, that moved out of the valley after 17 years there and 12 years investing in startups. I had a lot of arrows in my back and I had seen a lot of it invested in a number of semiconductor startups. So I knew how hard it was, I knew what heartache it was and how prone to failure it was. So when our mutual friend said, Ben and Dave were trying to start a semiconductor company I said man I would love to meet these guys because I want to talk them out of it and save a lot of heartache and probably save their marriages and everything else because I’ve seen how these things can go wrong.

RICH: Hang on one second, let me just ask a really personal question. Dave, are you still married?

DAVE: I still am.

RICH: Dave, you obviously got the better of that discussion because you talked Brendan into coming over—not only did he not talk you out of it, you talked him into running it!

DAVE: That’s right, haha!

JEFF: Clearly, Brendan, you need more therapy. You’re a recovering venture capitalist syndrome, had not been fully treated—that’s the thing about us, though, Rich. Even the two of us. It’s unbelievable. Just when you can be sitting here saying, oh my god, I can’t take it anymore, I’m getting beat up, the technology is not working, oh my god, the pricing pressure in the market, oh my god, the competition, we are done, we are finished. All of a sudden walks in the door—hey, what do you think of this? Oh, that’s great, let’s go!

RICH: Exactly, you John Belushi your way out of the room.

JEFF: The indomitable spirit of the great entrepreneur. So Brendan, obviously you did get talked into running the company. How in the heck did that happen?

BRENDAN: Yeah, that is a good question. When I first met with these guys, I had kind of a shortlist of reasons why you don’t start a semiconductor company. A, it takes too much money. B, you’ve got to be at a minimum ten times better on paper than what Intel or Qualcomm or Texas Instruments is doing, you can’t be two or five times better, you got to have an order of magnitude of improvement as a starting point because no one is going to buy you if you don’t. By the time you actually get all this encased in silicon—meaning from design on paper or design from computer to actually working silicon, that 10x is going to be a 5x or 2x.

I had a list of reasons why it was really hard to start from ground zero and be successful. And before they told me anything about what they were doing I said look, let me disclose my bias here. I don’t think you should do this. I want to hear what you’re doing but let me skip to the end and tell you what I’m going to tell you. It’s going to be super hard. I just want to caution you as to how hard it’s going to be. They said, wow, thanks for the honesty, that’s super helpful. Let us tell you what we have done.

And so they started listing off what they had achieved. They had already demonstrated all of this in Silicon meaning they designed and demonstrated a semiconductor that was operating not 10x better but 1000x better, than anything available on the market. That was kind of a head snap for me.

JEFF: You were kind of doing, hmm, as you were checking off these things.

BRENDAN: Exactly, exactly. And they weren’t what I would call the typical academic professors who had theorized that it was 1000x better, they had actually built a semiconductor, manufactured a working semiconductor in a commercial process that was 1000x lower power. And that’s, that’s a huge game changer right there. It was beyond proof of concept. The other big thing in semiconductors, this gets a little bit into the weeds is they were not depending on moor’s law to get this performance advantage. They were not relying on the cutting edge 14 nanometer process to get low power. They were in 130 nanometer process—so four generations old at that point in manufacturing so all of the magic for this low power achievement was in brilliant circuit design, innovative architecture, stuff that was not easily comparable, when they move to the next manufacturing process.

There was some real magic there obviously, that got me pretty enthusiastic.

RICH: So they wove an incredibly compelling tale and Brendan at that point was confronted with his wisdom versus his excitement, it was just incredibly compelling.

JEFF: Brendan had to call his wife and said, honey, you’re not going to believe this.

RICH: You’re going to divorce me.

JEFF: I went to go talk to these nice guys out of this thing—you know what we’ll just talk about it later.

RICH: Exactly. We’ve got to go out to a break here but when we come back from the break we’re going to talk about the genesis of the startup company and it’s called PsiKick and we are going to talk about how they created this and Jeff, they’ve raised millions of venture capital dollars from some of the most sophisticated venture capitalists in the world. And they are on a path now and on a true path to make a huge impact. When we come back from this break, you’re listening to StartupNation Radio.

RICH: All right, welcome back to StartupNation Radio. We have a problem solvers show today on our special series that focuses on extraordinary technology and research that spun out of universities and national labs and resulted in startup companies that are making a sweeping change in the marketplace. We’re talking to doctor David Wentzloff, he’s a professor at University of Michigan and the co-CTO of a company that we’re introducing to you in this portion of today’s show, and also the founding CEO of that company, Brendan Richardson. Welcome back to the show guys.

JEFF: Great guys. Suffice to say, we’ve heard now, you guys decided to make a move, you’re going to form a startup company. Obviously you got to do the same kind of basic things any entrepreneur would do at that point, you guys got to come up with a business plan. Right? And you got to agree on it, lock heads on it and agree on what are we going to do with this great research, what’s the product going to be, who is the market, what’s the problem we’re going to solve specifically, what’s the first thing we’re going to address, how do we really the resources, who are the people required. Those are all the basic things anybody would do at that point. Who took the lead at that point, Brendan? Were you charged with pulling all that together?

BRENDAN: I would say it’s highly collaborative. I was organizing maybe our thinking about it but the first thing we needed to do was raise the money so we could begin to hire some of the circuit designers that had trained under Ben and David, research groups, to come and join the company as the first employees and work the technology out of universities and into the company, and prove to investors that we could actually design chips inside the company and not just in universities.

RICH: I just want to pause here for a second, Jeff. Many times with these kinds of companies, what’s called rounds of investment are required in order to get a company off the ground, growing. You don’t raise all of the money required because money is expensive at this high risk stage. What Brendan is describing to us is the raising of a first round of investment.

JEFF: He described it as the first thing we needed but of course the first things you have to do is get the business plan together, figure the business out, how we’re going to make this happen, we got to figure out how much capital we need in order to achieve the objectives you started hiring these key people. There’s another thing that had to happen too—you had to get the technology out of the university environment and into the ownership of the company, did that happen I assume by license agreement?

BRENDAN: It did, yep, it was a license agreement, two license agreements actually because IP Michigan and IP Virginia so we had to create and negotiate two identical license agreements with each university to get access to the technology and then hire some people to basically execute that technology as a company rather than as a research lab and university. That took a little bit of money and we were able to convince investors to back that part of it and that heated us up to be able to go raise a very sophisticated venture capital firm out on the west coast.

RICH: Jeff, I just want to point out, these licenses that these universities spin out, gain, they are what are called technology transfer offices that every university has and there has been a wakeup call that has gone out over the past decade or two where universities are very actively participating in trying to move technology from inside those laboratories, out into the marketplace. What’s the benefit? As Dave, you said earlier, you want to see impact, so that’s a big benefit in the market, impacting people’s lives but they also get royalties.

JEFF: The university does, right.

RICH: Sometimes they get equity ownership, so those are the forms of compensation that incentivize universities to move this technology out into the marketplace and that’s what UoM and UVA did in this case.

JEFF: Great, so now you guys are up and running, you’ve got your first round of financing, you know, beyond seed, beyond first round of venture financing. Where are you now and where does this go and the ultimate question is when do we start making some money?

BRENDAN: Haha, that is a 65 million dollar question.

JEFF: I thought it was 165 million.

BRENDAN: 65 million in the first year.

JEFF: Got it, love it, good.

BRENDAN: So we just hired in the last several months a really, a true CEO I would say, an experienced semiconductor CEO based in the valley who has built billion dollar semiconductor businesses from the ground up and he has taken a company to the next level and really driving towards first chip revenue later this year, so we’ve gotten the technology to the point where it’s commercializable but we really needed somebody with deep experience in this industry to kind of take it to the commercial stage and that’s happening as we speak.

RICH: Brendan, let me ask you a pointed question. Was there any hesitation on your part to give up the CEO role or was this something you welcomed?

BRENDAN: Uh, no hesitation at all and I think Dave will verify that the plan from the very beginning was to have me as an interim CEO and then get to the point where we could hire somebody with a lot of experience. As I said, I wasn’t a serial entrepreneur—I had seen this as a VC, but I had never run a chip company or any company for that matter. So it was really getting to the point where we could attract a CEO with this level of experience.

RICH: Dave, I know how important it is for you, Dave, that the work be promising and that you feel like you’re on a path to making that impact and profit in the future but I know it’s important to you also what kind of company you’re a part of and my conversations with you, Brendan, that’s a big priority too, you’ve established a culture together as a founding group. Now you bring in as heavy weight CEO leader, I am sure is very exciting to the company but are you guys concerned about your culture changing? Are you worried, are there new risks and dynamics you’re going to be dealing with?

DAVE: Absolutely not. I mean we were during the CEO process, that was certainly that as we were meeting with candidates we were evaluating, in addition to their business jobs and their ability to take us to market, we wanted to know how they would gel with us, with the rest of the team, and just make sure we were all on the same page and Phil was a perfect fit on all fronts.

RICH: So Jeff, one of the takeaways here for me and I want to call this to every startup’s attention is getting the team culture right is absolutely critical. You get a bad actor inside your small little company and it’s poison.

JEFF: The team, the team, the team.

RICH: It’s got to be that incredible team, everybody moving in a direction, and harmonious.

JEFF: Taking their best spot. I know we’ve just got a few minutes left, I want to understand now, the go-to market strategy for the company is what?

DAVE: That’s a great question. So the go-to market strategy is to begin selling these extremely low power chips in the form of a module that enables companies that are on the cutting edge of developing internet of things applications to do it in a way that’s battery less. You can build systems where the center nodes require 0 maintenance from a battery or power perspective.

But ultimately we don’t want to be just a chip vendor because it’s tough to be a chip vendor, gross margins are always under pressure, we really want to move up the stack and begin to build systems ourselves that are enabled by these self powering chips that we developed.

So that may sound like a contradiction, there’s a very fine line to walk in. we don’t want to go sell chips that ultimately we can be with ourselves. We do want to get into the market selling silicon but towards companies that are developing some applications that are sort of cutting edge. But ultimately we’re going to find a vertical or verticals where we can go further up the stack, as they say, and develop systems ourselves.

JEFF: And you would probably continue to get intellectual property protection on those systems and then you can get higher margins on those systems and that’s what the company really starts to accelerate both in terms of sales and in value. That’s really great. Guys, what a great story. You guys definitely are addressing a big problem.

Thanks so much for sharing the story. We’re going to continue to check back with you guys. Check the progress on this company, it’s really exciting stuff. Nothing bigger than this, internet of things right now.

RICH: It is a major transition for us in the marketplace. Professor David Wentzloff and Brendan Richardson, thank you so much. Jeff, you know who I’m really worried about though? I’m worried about that energizer bunny having to go on unemployment, because he’s going to be out of a job.

JEFF: He is going to be out of a job but imagine what’s coming. Just imagine the possibilities. It’s a good tradeoff worth making. Listen, remember out there, if you’re listening to this show, check out StartupNation.com, go to the radio tab, and you’ll find additional information about this show that’ll be really valuable, it’s a further opportunity for you to learn and engage, we encourage you to do that. We want to get your dreams started, hey I want to make a special callout to our production team at StartupNation Radio, Paul Bologna, Chris Nierhaus, and the great Mark Blackwell, thanks so much guys for helping us make this show happen.

RICH: Alright Jeff, between this week and next week, let’s start it up!