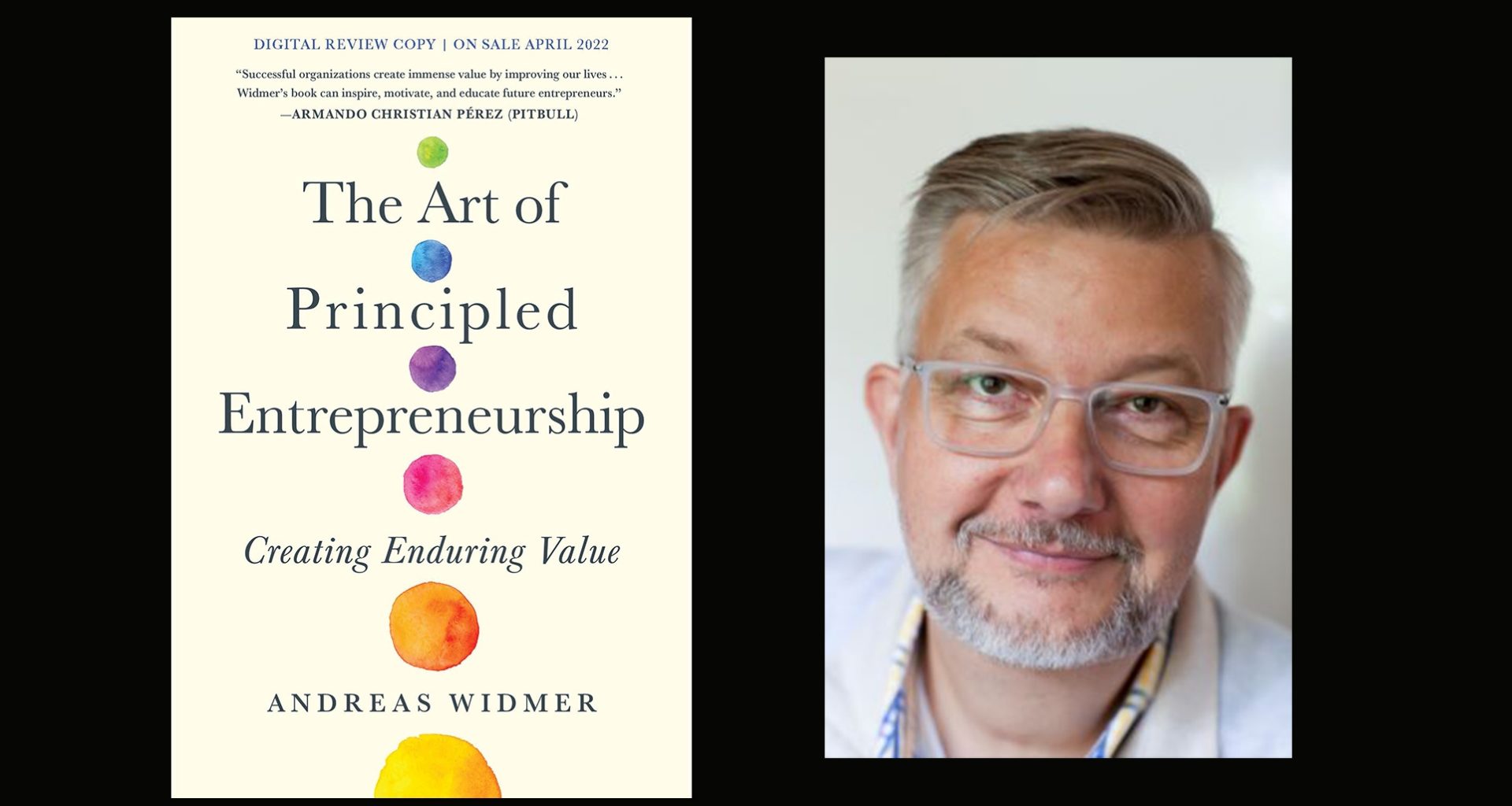

Excerpt from “The Art of Principled Entrepreneurship: How to Create Enduring Value” by Andreas Widmer (Matt Holt Publishing, 2022).

It’s difficult to teach an art. Perhaps the most one can do is describe Principled Entrepreneurship and the let students gravitate to or away from it.—Art Ciocca

When I’m asked the classic question whether or not entrepreneurship—or Principled Entrepreneurship, in our case—can be taught, I always hesitate to answer because I’m not sure the questioner has the time to hear the full answer. I usually give the short answer, which is “No…and yes…and it depends.” Entrepreneurship is often defined as “the activity of making money by starting or running businesses, especially when this involves taking financial risks; the ability to do this.”

With this definition, the answer to whether it can be taught would be no. The ability to start a company and having the nerves to handle the financial risk is a natural talent. Not everyone has the disposition to handle that kind of uncertainty and risk. Teaching it would be unnecessary and impossible. I would suggest, however, that the Oxford definition of entrepreneurship provides only half of what is involved and is a bit wrongheaded. In my experience, entrepreneurs are actually not much more risk-tolerant than the average person. It’s just that they perceive an opportunity, they see a solution that others don’t, and so, to them, the success of their business is far more certain than to an outsider, someone who doesn’t see or understand the opportunity they see.

The ability to start a company and having the nerves to handle the financial risk is a natural talent. Not everyone has the disposition to handle that kind of uncertainty and risk.

In that sense, they don’t necessarily take more risks than others. Or rather, their risk taking is real, but is balanced by the possibilities they see. If we saw what they saw, any one of us would do what an entrepreneur does. We all act on something we feel certain about. The question is, are we trained to do so in order to create value? Not all ideas create value, and not everyone who starts or leads a business is an entrepreneur. In fact, entrepreneurs don’t all start or lead companies, as we said in the previous chapter. In my experience, entrepreneurs are people who do more with less. Principled Entrepreneurs do this toward a specific aim. They are disruptors or change agents who improve the system positively. They might have an insight they recognize and—whether they run a company, manage a team, or are an employee somewhere in a large organization—they act on that insight in a way to improve things around them. They make the world a better place by creating value for others through human excellence. In this sense, entrepreneurship can and ought to be taught.

We can teach students how to gather information, how to generate original insights, how to create customer value through human ingenuity, and how to develop the conviction and confidence to follow through. After all, as we’ve said, entrepreneurship is more an attitude than an aptitude, an application of our free will—the most human of all aspects of our nature. And the exercise of our free will does not have to be taught per se, because everyone has it. But dedicated instruction can help us strengthen the entrepreneurial attitude and teach us how to harness our wills consistently for human excellence. Learning requires, however, that the student be an active participant and not just a mere spectator on the journey.

Entrepreneurship is more an attitude than an aptitude.

So, it depends on the student whether or not entrepreneurship can be taught. In the final analysis, yes, entrepreneurship can be taught, but it’s akin to teaching someone to play the piano. It is most effective with people who have a natural talent to begin with. At most U.S. schools, entrepreneurship education has been done very poorly. In his book, “Burn the Business Plan,” Carl Schramm cites Syracuse University professor Mike D’Eredita, an Olympic rowing coach and accomplished entrepreneur: “If we trained our Olympic athletes like we train our entrepreneurs, America would never win even a bronze medal.” Schramm goes on in the book to describe ten lessons for aspiring entrepreneurs and their teachers to keep in mind as they teach entrepreneurship. He illustrates each of his points with role models, and throughout he insists that action based on right thinking is more important than a beautifully written business plan.

Entrepreneurship is a method and a mindset, more than a mere process. Therefore, entrepreneurship education has to pay adequate attention not just to the theory of entrepreneurship, but to the nature of the human person and the purpose of the market economy. This is where education of Principled Entrepreneurs has to start: right thinking leading to the right action. Teaching Principled Entrepreneurship is absolutely possible. It entails learning the fundamentals of human dignity, value creation, and the free market economy. It involves a balance of theory and praxis. It takes the student on a journey of self-discovery, self-control, and self-actualization. In this field of study, no one is simply the teacher; we are all students of Principled Entrepreneurship because it is never done. The path is the goal.

I like to tell my students that no one is an overnight success. Rather, we fail into success, as long as we make each failure a learning opportunity. This simple exercise of creating their “first business” serves better than any lecture I could give or any book I could recommend to have someone experience the true purpose and motivation of business. Business is not selfish but inherently other directed. A business has to offer a product or service that its target customers are willing to buy. Business starts with putting myself in the other person’s shoes to see the world from his or her perspective. That is the substantive difference between selfishness and self-interest. You can learn empathy only by “doing it,” that is, by practicing satisfying customer needs and creating value for clients. That is a key focus of our class: teaching the students to work from the customer backward. We want them to learn that a value is added when we create real value for others from our excellence.

Originally published May 24, 2022.