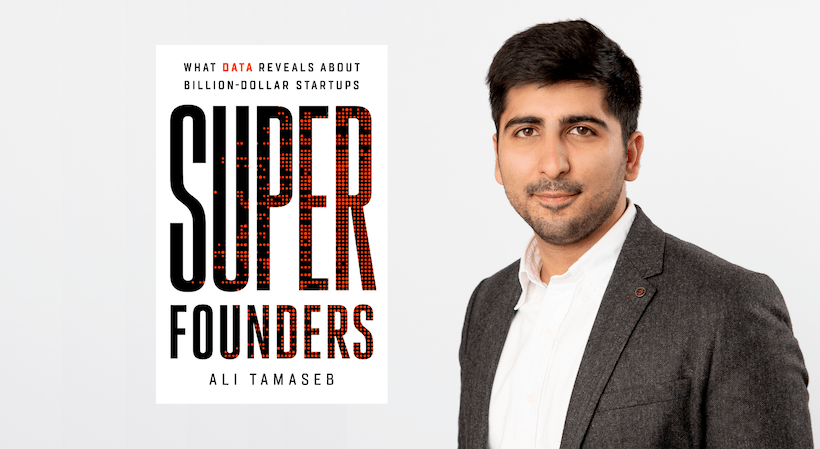

The following is excerpted from “SUPER FOUNDERS: What Data Reveals About Billion-Dollar Startups” by Ali Tamaseb. Copyright © 2021. Available from PublicAffairs, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

In 1995, General Magic, the startup company where Tony Fadell worked, built an early version of a smartphone. The hybrid telephone-computer was unlike anything the industry had seen before. But it never caught on — the technology for touch screens was in its infancy, the processors consumed a lot of energy that strangled the battery life, and very few people were using email. When Apple introduced the first iPhone, 12 years later, most of those problems were alleviated. But by then, General Magic was long gone and its smartphone mostly forgotten. Apple wasn’t competing with General Magic, but it wasn’t the first company to work on the smartphone idea either.

12 Keys to Starting and Growing a Side Hustle for Extra Income

Many billion-dollar companies are famously built on recycled ideas. At least eight companies tried to build a search engine before Google, with various levels of success and failure. Social networks existed a decade before Facebook, and companies had offered online storage before Dropbox. Instacart, the grocery delivery app, succeeded in 2012 by doing something similar to what Webvan — a startup with a similar idea that failed during the dotcom bust — tried to do in the year 2000.

Great ideas work because they’re great ideas, but also because they’re introduced at the right time.

Timing is one of the key ways founders explain their success or failure. In a survey done by the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, when 900 venture capitalists were asked about what they considered the most important factor in the success of their portfolio companies, timing came in second. (The first was the makeup of the team). After Apple added the App Store to the iPhone, companies like Uber saw an opportunity to leverage the device’s internet and GPS capabilities. Instagram was made possible by the proliferation of high-quality smartphone cameras, and Snapchat by the proliferation of front-facing smartphone cameras. PayPal grew because eBay was growing.

Venture capitalists often overestimate the value in being first. Some will even reject an investment opportunity because “the idea has been tried a dozen times before and never worked.” The problem, as they see it, isn’t competition, or how many other companies are currently working on the same idea; investors simply get skittish about sinking money into ideas that have failed before. In practice, however, it seems as though some ideas repeat every now and then, and they finally work when they align with the right market dynamics.

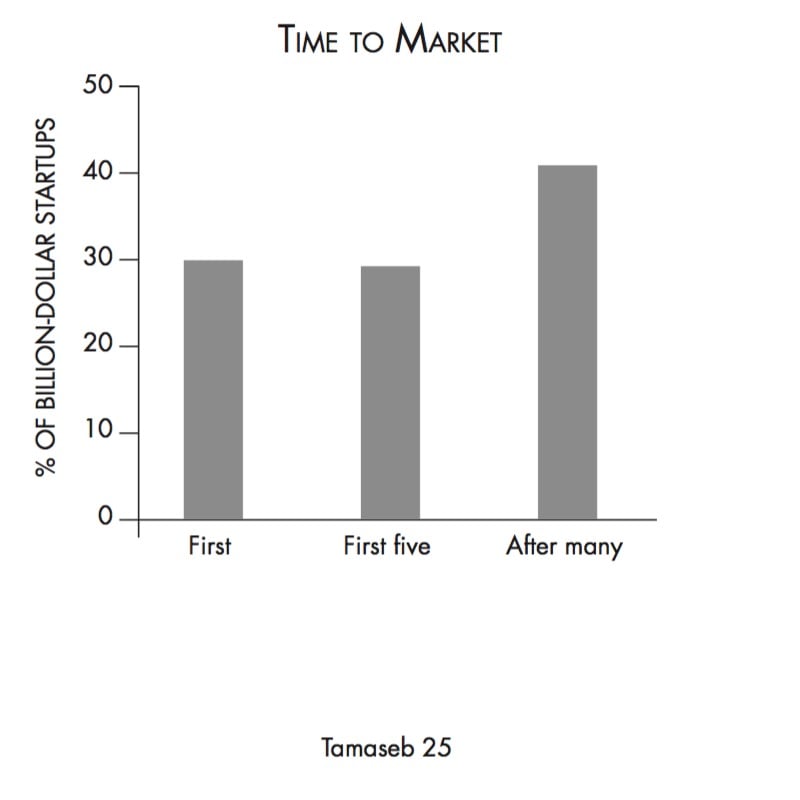

When I compared the data related to timing between billion-dollar startups and the random group of startups, no single obvious pattern differentiated them. Some billion-dollar companies were first to market, some were within the first five companies to try an idea, and others were late. This means that successful companies could have been made on the very first iteration of an idea, within the first few tries, or by building a repeatedly built idea — and in none of these cases were they more or less likely to succeed. The question of timing seems to be essential, and one of the hardest to crack in the code of success.

Related: How to Maximize Your Profitable Growth in Your Chosen Market Segments

If you’re a founder, it’s important that you foresee and understand the external factors that affect a company’s timing: inflection points, enabling technologies, changes in regulations, new market segments, and other fundamental behavior shifts. These are the things that have led to the success of many billion-dollar companies, rather than their being first or last to try an idea. Elad Gil, the angel investor, worked on Google’s mobile team early in his career. Back then, “all the telecom carriers — specifically the European ones — would charge one dollar for every time you used GPS,” he told me. Apps that rely on location data, like Uber, couldn’t have existed. It simply would have cost too much. That changed with the advent of the iPhone and the rise of Android, which broke up the oligopoly of the mobile carriers. As Gil puts it, “The ‘why now’ for Uber was that the industry structure shifted, and in particular the economics around GPS and other data services shifted.”

For founders, being ahead of time is essentially picking the wrong idea.

Sometimes, the timing is right when the prices of components fall low enough to enable new consumer products. Pete Flint, managing partner at the venture firm NFX, points out, “Tesla and electric cars became much more viable once the cell phone boom drove down prices of batteries.” At other times, it’s the reverse: the timing is right when prices are inflated. “Expensive cable subscriptions and record albums in part fueled the rise of streaming companies like Netflix, Spotify, and Hulu,” Flint wrote. “High, inflexible costs for contract labor and stagnant wage growth in parts of the economy gave birth to the gig economy and startups like TaskRabbit, Postmates, and DoorDash. And some macroeconomic forces — like the recession — created the sharing economy. It’s no coincidence that Airbnb and Lyft popped up in the years following the financial crisis.”

For one more example, look to Plaid, a financial technology company that was acquired by Visa for $5.3 billion. Using a set of application programming interfaces (APIs), Plaid helps app developers collect financial data from a user’s bank with the user’s permission. A company that wants to lend money can use Plaid to easily connect to a borrower’s bank account and check the balance.

Sign Up: Receive the StartupNation newsletter!

The ability to collect such data from banks wasn’t possible until a regulatory change. The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, passed in July 2010, created a series of financial reforms designed to avoid another crisis like the one in 2008. A small part of this law, Section 1033, says that banks must “make available to a consumer, upon request . . . information relating to any transaction, series of transactions, or to the account” and “in an electronic form that can be used by computer applications.” Those few lines created an opening for a company like Plaid to launch just a few years later, in 2013. Plaid leveraged the regulatory change to forge relationships with banks and build the infrastructure to collect this kind of data from them, and in return to share such data with other companies like lenders, financial-management apps, and wealth-management platforms.

It’s clear that timing matters to the success of startups. Great VCs typically ask the question “Why now?”

There are plenty of reasons that good ideas fail: it could be that the technological infrastructure doesn’t yet exist, or that customers simply aren’t ready.

This way of thinking can even be a useful exercise in coming up with startup ideas: look at ideas that were tried before but failed. Go talk to the founders of those failed companies, and attempt to understand the real reason they failed. Sometimes the reason is that the technology didn’t exist back then, but often that is not the case. More typically, the problem is market-participant incentives, unit economics, or a chicken-and-egg problem that is hard to solve. Spending time researching and understanding why your idea has failed before is perhaps one of the best investments of time you can make. If you are convinced and have a valid reason for why those failure points are not going to happen this time around, and if you can identify a trend or inflection point that will help, then your idea might be something to double down on. Good ideas pan out eventually. You just have to introduce them at the right time.

Originally published May 17, 2021.