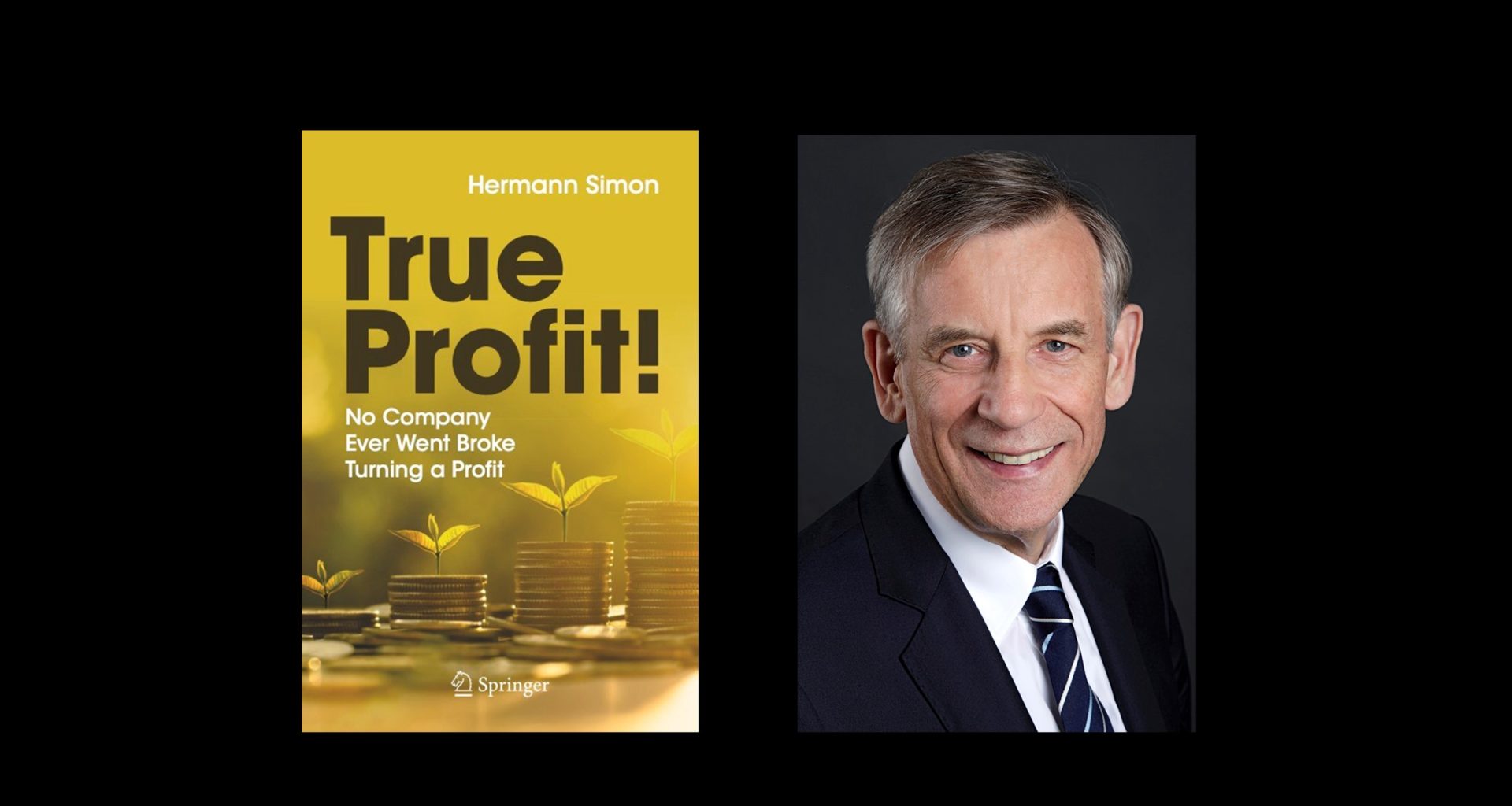

This is an adapted excerpt from “True Profit!: No Company Ever Went Broke Turning a Profit” by Hermann Simon. Copyright 2021 by Springer.

“I’m for profit maximization!”

If you want to infuriate large portions of society and turn people against you, uttering that sentence is a very effective way to do it. Few phrases are more explosively controversial than “profit maximization.” Some people even go berserk when they hear the word “profit.”

This kind of aggressive reaction seems to be universal. The maximization of profit—or perhaps worse, the maximization of “shareholder value”—is considered by many observers to be the root of all economic evils. Of course, most rank-and-file employees oppose profit maximization. But beyond that, it doesn’t matter whether the listeners are teachers, doctors, lawyers, or civil servants, not to mention the critics among political scientists, sociologists, or philosophers. There isn’t even general consensus in favor of the “profit” concept among businesspeople.

So what is profit anyway?

The simplest and easiest-to-understand definition is the one above: profit is the residual amount left over after a company has met all its financial obligations. But the reality is unfortunately more complicated.

There are a variety of definitions for profit, and it is not an exaggeration to say that some of these definitions are confusing or even misleading. When we talk about profit, we should know exactly what we are talking about. Otherwise it is easy to be deceived.

Profit depends on three drivers, namely, price, sales volume, and costs. Costs break down into fixed costs and variable costs. If a country imposes a sales or value-added tax (VAT), revenue is usually expressed without those taxes included. But some practices deviate from this standard. In addition to the operating revenue and operating costs, financial aspects such as the ones mentioned above (interest income, proceeds from asset sales, etc.) can flow into the profit calculation. Revenue occupies the first line in standard financial reporting, which is why it is commonly referred to as the “top line.” Profit after taxes—the true profit in line with our definition above—typically is the last line of the report, or the “bottom line.”

An insightful perspective is to interpret profit as a cost. “Profit is the cost of survival,” Peter Drucker once said. According to his view, profit comprises three types of costs:

- Costs of capital

- Costs of business/entrepreneurial risk

- Costs of securing future jobs and pensions.

In this sense, profit should not be understood as a residual that hopefully has a plus-sign at the end of the business year. Instead, profit should be factored in upfront, like cost, in order to secure the company’s survival.

Profit is what a business or entrepreneur can retain after fulfilling all obligations to third parties. By the simplest definition, profit is the difference between revenue and costs, in some cases adjusted for other aspects unrelated to business operations.

Profit is an important component of value added. Profits are interpreted by some authors as the cost of survival. More broadly-defined terms for profit have become popular, but they include factors that mask the determination of true profit. They should be viewed with caution.

Profits can be expressed in absolute terms or in the form of returns. In the latter case, commonly used metrics are return on sales, return on equity, and return on assets. There are also terms such as normal profit and economic profit which take the opportunity cost of capital into account. If a company does not recover its cost of capital, it may report an accounting profit but does not generate an economic profit.

A company can be liquid, but not profitable. This case is quite frequent in early stages. Conversely a profitable company can be illiquid and end up insolvent. This case is rare. Cash flow and liquidity-based metrics play an important role in practice, but they offer no direct insights into a firm’s profitability. Over time, however, profit and liquidity tend to go in the same direction.

Do you see now why we need clarity and focus when it comes to profit?

In press reports and meetings, it is often not precisely clear what kind of profit is being discussed. In the finance community, certain profit measures have established themselves, but they have nothing in common with the definition of true profit, namely, the residual amount of money after a company meets its obligations. One is inclined to think that this jargon arises from intentional obfuscation tactics so that the general public—and in some cases even insiders—struggles to understand the different concepts and terms and to distinguish among them. This jargon is at least partially responsible for the widespread confusion and misperceptions about the profit situation of individual companies or industries.

The goal of this article is not to engage in a comprehensive examination of profit calculations in all their complexity. That is what specialized accounting literature is for. My goal with these definitions is to provide the reader with brief explanations of the most common profit terms and concepts. But I leave entrepreneurs with one recommendation: In any discussion when the word “profit” comes up, you should ask, for the purpose of clarity, what that term includes and excludes.

Here’s why every entrepreneur must decide what profit means to them

The prospect of making money represents the most important, though not the only, incentive to develop innovations, found startups, improve efficiency, generate growth and create jobs. Profits are a prerequisite for the long-term survival of a company. In the long run, there is no liquidity without profit. Sustained losses will inevitably lead to bankruptcy, job destruction, debt defaults and lost tax revenue.

One pleasant moral and ethical effect of a capitalist-market economy is that profit begets freedom. Business owners who generate a profit reduce their dependence on banks, customers and suppliers. They can decide on their own what they do with their profits. They can distribute them, reinvest them in the existing business, build new businesses or donate them to a cause or charity of their choice. Profit grants freedom. The opposite also applies. The business owners who generate losses will sacrifice freedom and autonomy. Banks will restrict the entrepreneur’s leeway, and the company becomes increasingly dependent on every single order or job. Employees fear for their jobs, and the working atmosphere deteriorates. In the case of insolvency, the freedom of the owners and their business comes to an end, as a court-appointed trustee takes control. This outcome has left many entrepreneurs broke and broken.

Profits are a delicate topic. It is not an exaggeration to speak of a taboo, although this does vary by culture. In Europe, hardly any entrepreneurs willingly admit how much profit they earn, nor is it proper decorum to ask. Even in my days as a consultant, I was hesitant to ask about it at the beginning of projects. One prefers to talk instead about revenue, number of employees, and market share while sidestepping the question of profit. Closely held companies rarely provide profit numbers in their press releases. This is somewhat different in the United States and Asia, but still not widespread.

Treating profit numbers as taboo has some plausible reasons. Companies and individuals shy away from the topic when their profits are either relatively low or relatively high. If margins are low or negative, exposing that fact can cause business leaders to lose face, especially if they have previously highlighted their revenue figures. I have often experienced such situations. The question “And how does profit look?” draws either a lot of hemming and hawing or an embarrassed silence. Rarely does someone cite a concrete number. Conversely, if margins are high or very high, publicizing them could put the business leaders in a precarious position. If suppliers or customers catch wind of the high margins, they might demand a larger share of the pie. A company with high margins needs to have a strong market position in order to resist the demands of large customers. But sometimes the demands of customers are not as aggressive as one might fear.

Profit is a controversial and polarizing topic in society. But whether profit is the purpose, the consequence, or the essence of entrepreneurial activity is for me a completely academic question. Every entrepreneur must decide what profit means in his or her individual case. The hair splitting distinctions among the concepts of profit maximization, profit optimization, and profit orientation are not very helpful.

Profit orientation remains a constituent element of capitalism. The superior performance of market economies relative to other systems ultimately derives from the profit motive. Private companies have a responsibility to society to earn a profit. That is the only way to secure jobs, make investments and innovate. It is also the only way for a firm to meet its obligations to its employees and its business partners. Earning a profit must fall within the bounds of ethics and decency. But there is no doubt that in reality, sometimes these ethical boundaries are crossed. That is one of several reasons why so many intellectuals are critical of the profit motive.

Objectively speaking, the level of transparency regarding profits is relatively high nowadays, thanks to databases, internet access, and government reporting requirements. Nonetheless, the general public is not well informed at all about the true profit situation in the business world. Entrepreneurs avoid discussing their profits, regardless of whether they are high or low, because they fear the potential consequences: price pressure, loss of face, envy, or threats.

Profit maximization in the strict sense is not absolutely necessary. But in light of the often poor profit situation, many companies would be well advised to do a better job of tapping their profit potential. The focus should be on long-term profit maximization, not short term. This corresponds to the concept of shareholder value, which is often interpreted incorrectly and subject to baseless criticism. Profit is not the sole purpose or motivation for entrepreneurs and managers. But it is an indicator of performance and success, and is therefore an important motivator. In contrast, meager profits or losses lead to frustration and disappointment. Losses have brought down many companies, but no company ever went broke turning a profit.