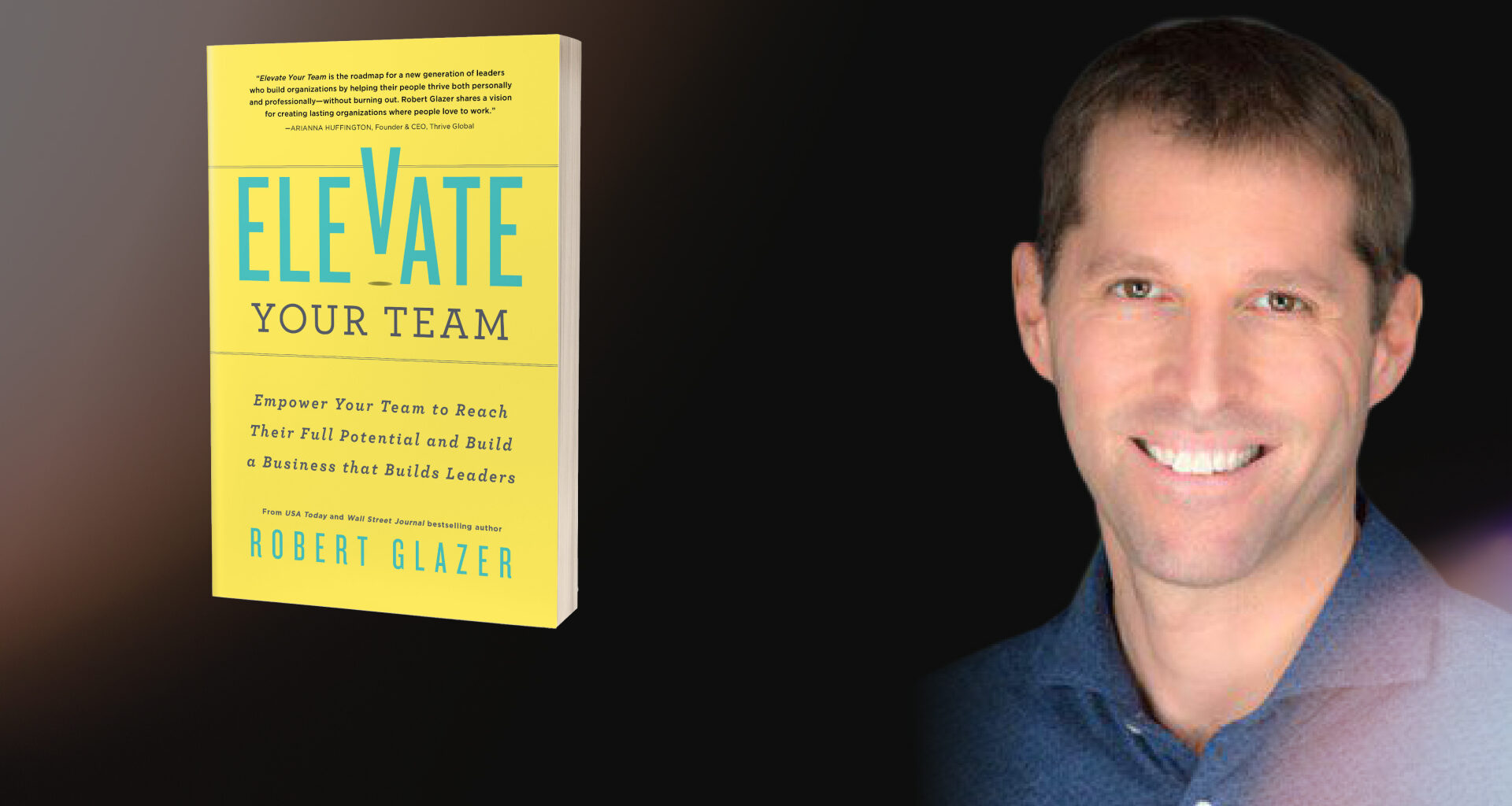

The following is an excerpt from “Elevate Your Team,” a look at organizational leadership, published by Simple Truths.

Jane shifted back uncomfortably in her chair as the words from her boss, Mark, sank in.

“This isn’t easy to say, but I just want to be really clear with you that if we don’t see a sustained improvement in your performance around the key issues we discussed today, it’s very likely we are going to be speaking about a transition out of the company.”

Jane finally understood the gravity of the situation, and Mark was able to confidently communicate a message that no leader looks forward to giving.

That’s when I interrupted and said “freeze” and asked the other 20 people in the room for feedback.

Level Up Your Digital Skills: Free This Week with Verizon Small Business

This was the last day of one of our advanced leadership training workshops, and we were doing a “difficult conversations” role-playing exercise. We crafted a selection of prompts that were based on real performance management conversation topics, and we assigned volunteers to act out each role—with one person playing the manager (Mark) and the other playing the direct report ( Jane). The conversation topics were ripped-from-the-headlines types of situations—complicated performance management conversations that all our managers eventually have to navigate and that many workshop attendees would likely need to have for the first time in their careers in the next year as new managers.

Even though these were low-stakes role-playing exercises, the fictional managers felt real discomfort and often struggled to communicate clearly and stay on script in the moment.

We’ve done this exercise multiple times, with over 100 employees at this point. As part of the session, we always have a volunteer pretend to be a manager who needs to inform their direct report in a check-in that their job is at risk if they don’t improve, and we have another volunteer play an employee who thinks things are going well.

Usually, the two have a cordial conversation where the manager references some things the direct report can do better and reminds them to improve their time management and communication precision. The result of that uncertainty is the employee assumes everything is going well overall, even though it isn’t.

That’s an outcome we most want to avoid, and it’s the impetus of the exercise. While the audience has read each volunteer’s prompts, the role-players themselves know only their side of the story, to imitate a real-life situation.

About 10 minutes into the conversation, I tell our role-players to freeze and ask the audience for their input. The first question I ask is, “Raise your hand if you think the manager has made it clear that the direct report’s job is on the line.” Every time, not a single hand is raised.

And now everyone clearly sees the communication disconnect that often leads to disaster: the manager thinks the employee has gotten the message, and the employee is on a path to being blindsided.

Giving this type of feedback and warning is extremely difficult. I know many seasoned leaders who absolutely agonize over these types of conversations, even after having been part of them many times.

While it’s understandable—and very human—to find these conversations wrenching, they are even harder if you haven’t learned how to have them. Plus, the pain that’s avoided by dodging these conversations is nothing compared to the damage that results when two people think they are on the same page about a crucial issue when they in fact are not at all.

Verizon Digital Ready: $10K Grants and the Skills Entrepreneurs Need

A new manager who spends hours contemplating how to deliver difficult news or loses sleep for a week before a conversation like this is wasting a lot of valuable time and energy that impacts their work in other areas.

That’s exactly why role-playing these types of conversations is so important—we want our people to practice these discussions in a low-stakes environment, and we want them to observe sample conversations to see what traps to avoid and what best practices to emulate. When the unfortunate but inevitable time comes to have one of these conversations, they will be much better prepared, less nervous, and hopefully able to achieve a better outcome for everyone involved. It could also mean avoiding spending 10 to 20 hours of extra time planning for a performance conversation or spending even more time cleaning up the mess after a poorly executed discussion.

This is another example of improving the operating system: getting a better outcome with less energy.

Building A Culture of Feedback

A culture with high intellectual capacity is highly dependent on consistent, direct feedback. A learning culture is by definition a feedback culture; one cannot be decoupled from the other.

If managers are not able to deliver feedback to help their teams improve—or if employees believe they can ignore feedback without consequence—there is a ceiling on the entire organization’s growth.

Think about learning to drive. In most places, a person must pass a written exam to get a learner’s permit. Beforehand, they study a manual to learn how the car works, read about how to operate the vehicle, and get a sense of the rules of the road. But a person who aces this test isn’t guaranteed to be a good driver, and they aren’t simply granted a license—they must also practice driving under the watchful eye of an adult driver who observes them and provides important real-time feedback.

The same is true in business—learning and training are valuable, but most meaningful growth occurs through real-world practice, mistakes, and feedback.

To keep your employees on a high-growth trajectory, you have to give them space to make mistakes and help them identify areas of improvement. Even the most talented employees have deficiencies, and these are often trapped in people’s blind spots, which is why they need them brought to their attention in a direct but respectful way.

I would go as far as to argue that the ability to take feedback well is also a virtue that should be sought out. At Scribe Media, a book publishing and marketing company, they teach not only how to give feedback but also how to receive it. One thing they teach is “assume feedback is about the work, never the person.” This helps people who receive feedback avoid being defensive. A manager never critiques the person (e.g., “You did bad work.”) but instead talks about the work they do (e.g. “This work is not up to standards. Let me explain why and how you can fix it in the future.”).

Scribe Media not only coaches employees—the company teaches their clients as well. For example, during the book cover design process, they coach author clients to give specific feedback and say things like, “I do not like having blue associated with my brand. I would like to explore other colors,” versus something like, “It doesn’t feel right.”

Feedback is a part of learning, and you can’t have a high-growth organization without it, which often involves direct, difficult, or uncomfortable conversations. Training your managers and leaders to successfully have these conversations makes a huge difference in building collective capacity and getting world class results.

This excerpt from “Elevate Your Team“ is reprinted by permission.