The following is excerpted from “The Science of Dream Teams: How Talent Optimization Can Drive Engagement, Productivity, and Happiness” by Mike Zani, pp. 29-35 (McGraw Hill, July 2021).”

Through the hot summer of 2018, Elon Musk, the founder and CEO of Tesla Motors, slept for nights on end at his assembly plant in Fremont, California. Musk had vowed that Tesla could gear up production of its Model 3 sedans, rolling 5,000 of them off its assembly line per week. Mastering production of the entry-level Model 3 was crucial to establishing Tesla as a major auto manufacturer. Musk had bet the company on it.

A year earlier, Musk had outlined a vision to turn Tesla from a niche maker of luxury electric cars into a mainstream powerhouse. To build the Model 3, he created a new type of manufacturing line, with robots taking over much of the work. The process was slow getting started, though, and by the summer of 2018, the situation was dire. Tesla had billions in debt coming due. Investors, who had bought in on his vision and driven the company’s valuation to the sky, were fleeing. Musk and his team, besieged by glitches and shortfalls, were adapting on the fly, adjusting components, taking robots off certain jobs and redeploying humans. It was nothing less than an emergency, which was why Musk was sleeping on a cot in his office and wearing the same clothes for days on end.

Think for a moment about Musk. He is one of the great visionaries of our age. As a co-founder of PayPal, he envisioned the future of digital payments. He went on to found SpaceX, a spacecraft manufacturer focused on colonizing other planets. And then, in an effort to save the planet we still inhabit, he founded Tesla and created a booming market for luxury electric vehicles.

Now consider the work Musk was carrying out in that factory. He was dealing with a million details: supply chains, schedules, work flows, the nitty-gritty of engineering. This wasn’t vision but details.

Was Musk born for that? Every company has jobs that require different skills and personality types. The challenge is to map out the skills needed and to position people where they can contribute the most. If Tesla planners had worked up a diagram for optimum deployment of human talent, Musk would be firmly in the CEO office, translating his vision into strategy and selling it to employees, investors and consumers alike. That’s his genius. Someone else, an extraordinarily gifted details person, most likely an engineer with Six Sigma Black Belt credentials, would be running the manufacturing operation. The right people in the right places — that is the essence of talent design thinking.

The purpose of talent optimization is twofold: first, to figure out the ideal blend of talent for the company’s mission; and second, to map the talent currently in place. This requires design thinking.

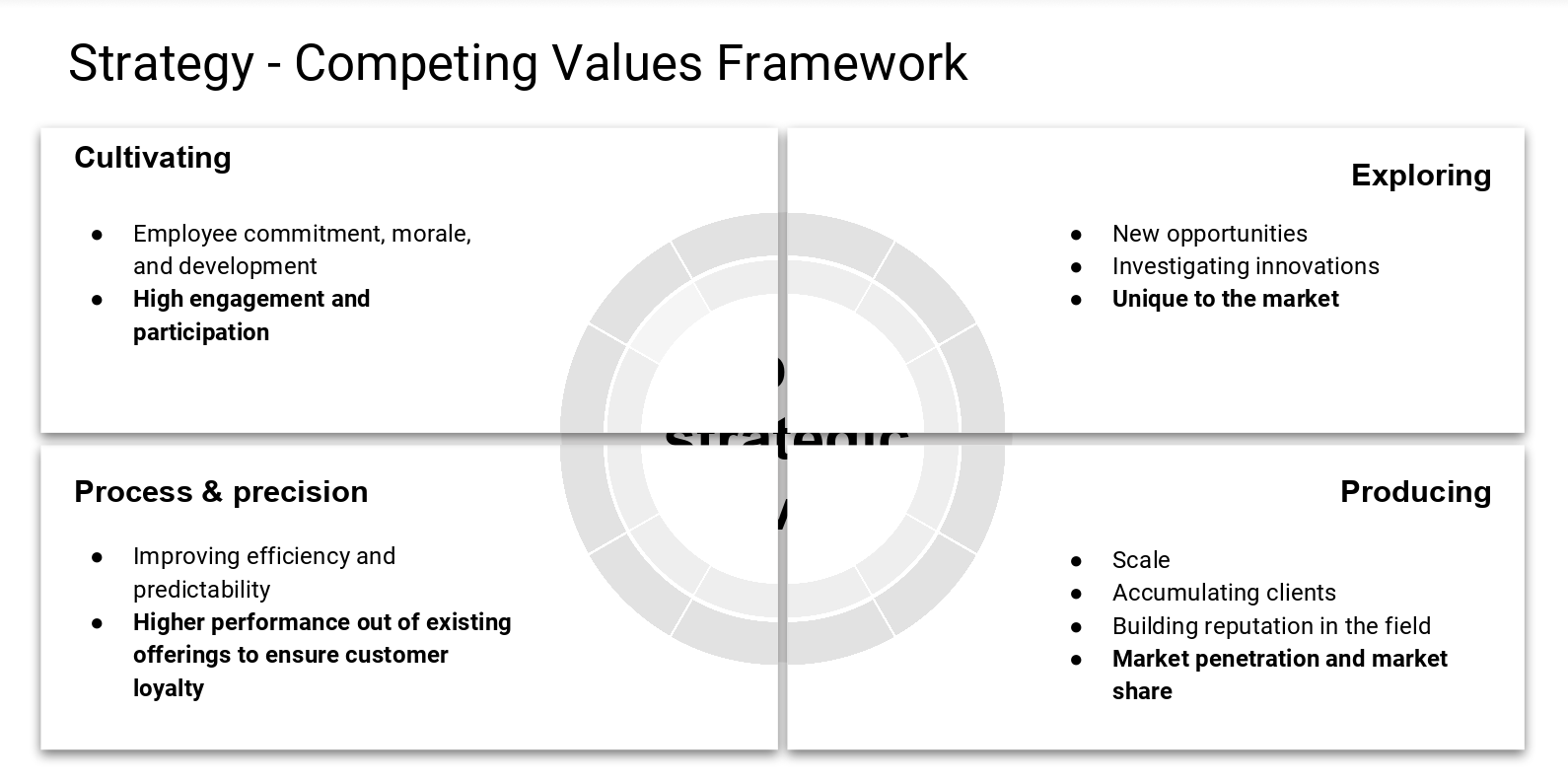

A good place to start is the competing values framework (CVF). Developed in 1983 by Robert E. Quinn and John Rohrbaugh, it models organizational culture and strategy. It divides the workforce into behavioral quadrants. The organizing principle of that scheme has become a standard in the industry. A number of assessment companies, including The Predictive Index, divide people into four similar groupings. Each version has its own nomenclature and its own nuances of classification and definition. They’re like different dialects within a common language. To keep it simple, I’ll use our company’s CVF (Figure 3.1). It’s the one I know best. But the process of creating a CVF for a workforce and using it as a design tool will also function on many of today’s platforms.

The fundamental metrics of the CVF are based on a person’s need for order (stability versus flexibility) and sociability (internally versus externally focused). People on the left side of the chart, both above and below, need more order or stability. Many of them pay greater attention to the details. Those on the right, by contrast, tend to be more flexible, looking more at the big picture. Switching the perspective to the Y axis, those on top are more externally focused on people while those in the lower two quadrants are more internally focused on running successful systems.

We call the resulting quadrants cultivating (teamwork & employee experience), exploring (innovation & agility), producing (results & discipline) and stabilizing (process & precision). This chart is, in effect, a map of people. It’s important to stress that there are no good or bad scores in personality profiles or on the CVF. Some people, you’ll see, end up close to the middle with no clear tag. That’s not a problem. They have a dose of everything. They are malleable and serve as valuable connectors.

Each person fits somewhere on the CVF. Consider Musk, for example. We haven’t given the assessment to him. But from what we know about him as a type, his profile would likely be in the extreme upper right corner at the combination of flexible and externally focused. He’s by nature an explorer. He tries new ideas, takes bold risks and pays little attention to hierarchy or rules or social mores. Others can clean up his messes.

Yet when he installed his cot in the manufacturing plant, Musk was moving to stabilizing, the exacting lower left quadrant. This is an area where process and procedure reign supreme, where details, schedules and supply chains matter a lot. Musk was working far outside of his sweet spot.

To his credit, Musk appears to be a talented enough leader to adapt. One of his skills is versatility. By late 2020, the Tesla factories were churning out half a million cars, and the stock shot up by a factor of seven. Musk was on top of the world. Yet for Musk, diving into the process had been torturous. In an interview with “Bloomberg Businessweek,” he called the experience the “most excruciatingly hellish several months that I have ever had.”

“The Science of Dream Teams” is available now and can be purchased via StartupNation.com.