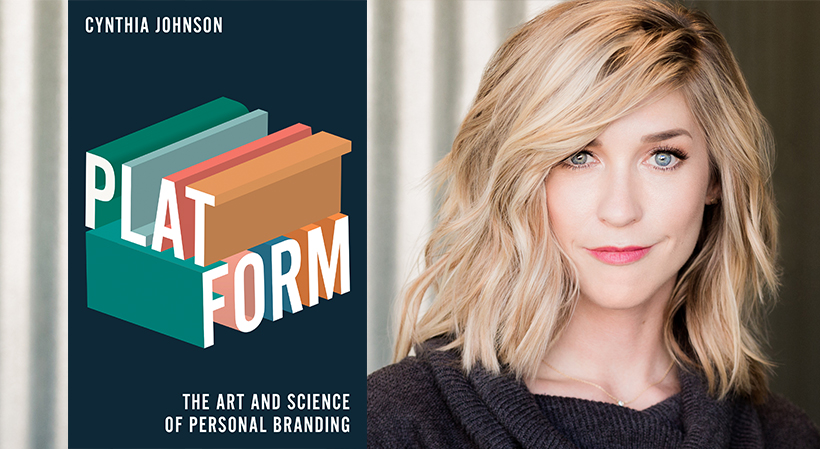

The following is reprinted from “Platform: The Art and Science of Personal Branding” Copyright (c) 2019 by Cynthia Johnson. Published by Lorena Jones Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.

Sarah Breedlove is considered the first female self-made millionaire. At the time of her death, she was worth $600,000, which would be about $8 million today. Sarah Breedlove was not an ordinary entrepreneur or millionaire by male or female standards. If you have heard of her, you probably know her as Madame C. J. Walker.

She was an American entrepreneur and philanthropist, as well as a political and social activist. She is considered the world’s most successful female entrepreneur of her time and one of the most successful African American business owners of all time.

Sarah was born into a family near Delta, Louisiana, on December 23, 1867, the youngest of six children. She was the first person in her family to be born into freedom after the Emancipation Proclamation was issued by President Abraham Lincoln in 1863.

Her mother died when Sarah was only five, and her father passed away two years later. She was an orphan at the age of 7. At age 10 and with no formal education, she moved in with her sister and got a job as a housekeeper. At age 14, she married a man named Moses McWilliams, presumably to escape her abusive brother-in-law. Imagine that you have no education, both of your parents are dead, you work as a maid, you are a black woman living in the South in the years after the Emancipation Proclamation, your sister’s husband abuses you, and to escape the abuse you end up married at age 14.

Related: 6 Women Who Blazed the Trail for Female Entrepreneurs

In 1885, when Sarah was 18, she gave birth to a daughter, Lelia McWilliams. Two years later, her husband, Moses, passed away. Now she was a single mother, who needed to quickly figure out what to do in order to take care of her daughter. So Sarah and Lelia moved to St. Louis, Missouri, to be near Sarah’s three older brothers. There she took a job as a laundress, earning less than a dollar a day.

Sarah’s goals were clear and simple: to make enough money for her daughter to go to school and get a formal education. For fun, Sarah would sing in the church choir and visit her brothers at the barbershop where they worked.

As she aged, Sarah began to experience the hair loss and dandruff common for African American women at that time. This was in part caused by the harsh hair-care products they used, many of which included ingredients such as lye that were found in soaps for washing clothes. Other factors that caused scalp issues and hair loss were a lack of indoor plumbing, infrequent showering, and poor diet. Whatever the reasons, Sarah was experiencing this problem, and she wasn’t happy about it.

She decided to take a job as a commission agent for Annie Turnbo Malone, the owner of an African American hair-care company. Since Sarah had hair and scalp problems of her own, she was very interested in these products. She began to learn about them and then to alter them. Eventually she realized that she had a better formula, and she started to develop her own product line. During this time, Sarah also married and divorced her second husband, John Davis. Sarah knew how to think for herself, both professionally and personally.

In 1905, while still working for Malone, Sarah moved with her daughter to Colorado, where she met Charles Joseph Walker, the man who would become her third husband. After they married in 1906, Sarah took her husband’s last name and started her own company with him. She changed her name to Madam C. J. Walker, to match the goal of the business. The title “Madam” was inspired by successful entrepreneurs and pioneers in the French beauty industry. Madam C. J. Walker began selling her products door-to-door, teaching other black women how to care for the style and health of their hair.

Later that year, Sarah put her daughter in charge of shipping products for the orders that she and her husband took as they traveled through the United States, selling their products door-to-door. The following year, they opened a beauty salon and school in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, called Lelia College of Beauty Culture, to train future “beauty culturists.” The couple would eventually open another salon and school in Harlem, New York.

Sign Up: Receive the StartupNation newsletter!

Just four years after launching her door-to-door business, Sarah opened her own manufacturing company in Indianapolis. Between 1911 and 1919, Madam C. J. Walker’s company employed thousands of women to sell her products. The women wore white or black skirts and carried black bags. They went door-to-door to sell not only the product but also the brand message.

All of the women Madam C. J. Walker employed as beauty culturists were taught “the Walker Method,” including how to budget and open their own businesses. In 1917, she created state and local clubs for her sales agents to participate in. She named her association the National Beauty Culturists and Benevolent Association of Madam C. J. Walker Agents (predecessor to the Madam C. J. Walker Beauty Culturists Union of America). The association held events and national gatherings, and gave awards to the saleswomen who sold the most, brought in the most new sales agents, and made the largest donations to their local charities.

Sarah Walker was also a philanthropist and visionary. In 1912, she spoke to the annual gathering of the National Negro Business League (NNBL) from the convention floor: “I am a woman who came from the cotton fields of the South. From there, I was promoted to the washtub. From there, I was promoted to the cook kitchen. And from there, I promoted myself into the business of manufacturing hair goods and preparations. I have built my own factory on my own ground.”

At the same conference the following year, Madam C. J. Walker was the keynote speaker. Her philanthropic work was extensive and effective. She donated to the building fund for the Indianapolis Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA). She also provided scholarship funds to the Tuskegee Institute, Indianapolis House, and the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, among other organizations.

Sarah Breedlove not only worked for the black community, she also worked to create an acceptance of it. She moved to New York City in 1918, where she became the assistant secretary for Negro affairs of the United States Department of War. She went on to become more and more political, giving speeches on political, social, and economic issues at conventions and events sponsored by black institutions Sarah Breedlove built an empire, empowered a community, brought positive change, and developed an incredible personal brand in a time when women had few rights and black women had even fewer. To give you an idea of the kind of world she was up against, she never had the right to vote in America despite her influence. Sarah passed away in May 1919, and women were granted the right to vote in June 1919 (ratified August 1920).

So the next time you start to tell yourself that you have it rough or that something is impossible, think of Sarah “Madam C. J. Walker” Breedlove. She stood behind her beliefs, her drive, and her love for community to build something out of nothing. She is a true role model for success and perseverance. She is the kind of person we should honor, and everyone should know her name.

“Platform: The Art and Science of Personal Branding” is available now at fine booksellers and can be purchased via StartupNation.com.

Originally published March 12, 2019.