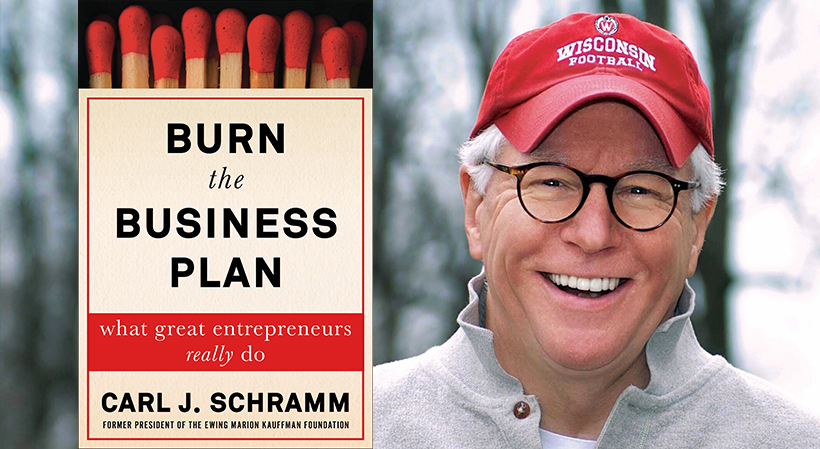

The following is excerpted from “Burn the Business Plan: What Great Entrepreneurs Really Do” by Carl Schramm. Copyright © 2018 by Carl Schramm. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Good companies don’t happen overnight

Of course, because of the media-driven narrative of entrepreneurial success, many entrepreneurs dream of starting an Instagram-like company, selling 18 months after launch to Facebook for $1 billion, or a WhatsApp, for which Facebook paid $19 billion when it was five years old. In fact, nothing could be less like the experience of the average startup. Instead of making their founders rich, you now know that most fail.

As the numbers suggest, formulating a successful startup takes time. When the founders of successful companies look back on their beginnings, the candid ones admit that they didn’t really know what they were doing, or where they were headed. This is an important observation as it suggests a different way to look at startups. In reality, every new company exists to search for a product that, developed through iteration and market testing, will achieve scale. While many aspiring entrepreneurs think that starting a company is all about one good idea, in fact, successful entrepreneurs know that their first idea was seldom what made their company successful. Just as in the big company environment, every startup has to constantly and continuously improve its products if it hopes to survive.

Google provides a good example. At first, it foundered in a sea of search engine companies. Many observers didn’t give it a chance in the face of Excite, Webcrawler, Altavista, Infoseek, and Yahoo. (Other than Yahoo, do you recognize those names?) It was not until Google’s founders, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, hired a professional CEO, Eric Schmidt, who in turn recruited Hal Varian, that the company found a way to make money. As an economics professor at Berkeley, Varian had developed the algorithms that enabled Google to devise targeted advertising. That business competence allowed it to rapidly rise to dominate the search industry.

It took Google seven years to be able to tell a convincing story to public investors. Similarly, many companies that we routinely think of as having enjoyed overnight success took at least ten years to develop what ultimately became their signature products. Go-Pro was 12 years old before it was in a sufficiently strong position to persuade public investors to back it. Microsoft and Oracle each were 11, and Amazon was 10. The average company that has sales revenue strong enough to interest public investors to buy its shares, to go public, is 14 years old.

These examples illustrate the shaky foundation of the build-to-sell premise of much startup planning. Rather than selling stock to the public or being acquired by a big company, most startups continue to be owned by their founders long after 10 years. From 2006 to 2016, an average of fewer than one hundred companies per year sold stock for the first time. Combine that number with the number of startups that were acquired by large corporations during the same 10-year period—fewer than an average of one thousand a year—and we readily see that the widely anticipated “exit strategy” that is required to be described in every business plan largely is a chimera. It happens to a mere fraction—fewer than .005 percent—of all startups.

This reality contradicts the widely held view that entrepreneurs start and sell companies as quickly as possible, and then move on to become legendary serial entrepreneurs. Few myths about entrepreneurs are quite as false as this one. Most entrepreneurs start one company. If their startups are successful, most founders work at it for the rest of their lives, building companies that provide both income and a means to build personal wealth.

Related: 7 Lessons for Aspiring Entrepreneurs

When you start a company, you are a boss

Every startup founder discovers that launching his company means that he has become an employer. In fact, one of his first challenges is to recruit talent. Unlike mature businesses in which managers may be able to substitute what are called capital goods (such as factories and equipment, including robots) for workers, most startups are relatively labor-intensive enterprises. In the beginning, entrepreneurs need other people to help make their ideas into concrete products. And, while established larger firms may have the luxury of making an occasional personnel mistake without hurting the organization in a noticeable way, a single hiring mistake can be fatal to a small startup. This reality requires that entrepreneurs learn to effectively manage people, and they must learn quickly.

Most entrepreneurs intuitively understand three useful rules of hiring. As noted, the first is that it is much harder to manage a workforce with co-founders. Problems of shared decision-making usually surface first in the realm of determining what skills are needed and in evaluating employee performance. Personnel disputes often become surrogates for larger disagreements relating to the direction of the company.

Second, entrepreneurs often are tempted to hire friends because they presume that they know them well. One of the most troubling discoveries for new CEOs is understanding that they don’t necessarily know their friends outside of the context of friendship, and that employment relationships, unlike friendships, can never be equilateral. Because the CEO has the power to fire every employee, she is not the coequal of any employee. While many startups appear to be marvelously friendly, informal, nonhierarchical organizations, the CEO, who carries more risk and worry than any other worker, knows that the company’s welfare must be her highest priority. When an employee who was first a friend is no longer of strategic value to the company, a firing almost always means the end of the friendship. Don’t hire friends—or, even worse, relatives— in the first place.

Third, unless it is unavoidable, it is a mistake to use company ownership—such as shares, options, or other types of interests in the company—to compensate employees. Because every startup that is striving for its scale opportunity is in a continuous state of flux, the relative value of every employee, one to the other, is constantly evolving. In startup companies, if ownership interests have been permanently vested in individuals who, over time, prove to be of less value to the evolving company, the presence of previously granted shares can severely limit the company’s flexibility in negotiating with potential investors, and even complicate the hiring of new employees needed for new endeavors. Some entrepreneurs who have been ill-advisedly generous with equity awards have found themselves in messy battles for ownership control, which almost certainly is the beginning of a death spiral for a young company. If employee equity grants can’t be avoided, this is the time to spend money on an experienced lawyer who can structure awards in a manner that provides maximum flexibility for the owner.

Sales are everything

Jeff Sandefer, who built a successful oil and gas business, runs the Acton School of Business, the only school in the U.S. that is dedicated solely to teaching entrepreneurs, and the only school that focuses on a sales and marketing, rather than a theoretical approach. Unlike accelerators owned by wealthy investors who are looking for promising new businesses, Sandefer does not invest in his students’ companies, does not profit from running his school, and refunds tuition if a student doesn’t succeed as an entrepreneur.

Operating a tuition-supported school, with a customer-satisfaction ethos, is apparent in his money-back guarantee, Sandefer keeps careful track of his graduates. Follow-up statistics indicate that his approach to entrepreneurship seems to be paying off. Sixty-three percent of Acton graduates start companies. Most wait nearly two years after graduating to throw the switch, time spent in additional research and development, including extensive testing of the target markets for their innovations.

Sandefer requires that every candidate spend three months selling door-to-door before he may matriculate. Knives, vacuum cleaners, frozen meat—it doesn’t matter. The experience makes an aspiring entrepreneur understand what salespeople know: selling is hard work. There are very few products that sell themselves; every product needs pushing. Selling, for an entrepreneur-in-training, is also the best way to learn how to improve new products. We see that lesson in the sales model that Jobs constructed for Apple: Talking and carefully listening to customers can guide product design and improvement, and successful customer input can drive sales.

Customers control the future of your startup. On more than one occasion, I’ve heard a failed entrepreneur say that his idea was “ahead of its time,” in other words, blaming the customers that he never had. Customers know what they want or need or like, and they will let you know what they find valuable. A corollary lesson about customer demand is to consider whether you are looking in the right place for your market.

Making money is what it’s all about

Richard Branson, the founder of Virgin Atlantic Airways and numerous other Virgin enterprises, once defined an entrepreneur as, “Someone who jumps off a cliff and builds an airplane on the way down.” Every entrepreneur understands this metaphor in very personal terms. Starting a company involves disturbing a career path, risking savings, living with debt, and suffering the possibility that family and friends will see you fail. Attempting to wrestle an idea into a successful business requires psychological fortitude. Not everyone is suited to the uncertainty, sacrifices, and loneliness that typifies the long period from startup to knowing whether a business will succeed.

This is why making money plays such a motivational role for entrepreneurs. If you are not starting a business to make money, go home. Making money is critical to the survival, much less growth, of your company, and pushing forward to achieve scale is the formula for financial success. Would you found a company if you didn’t see the potential to grab the golden ring?

Of course, in addition to wanting to make money, many entrepreneurs are animated by nonmonetary or psychological rewards. Imagine the enormous satisfaction of starting a drug company that produces a medicine to cure a terrible disease. Many entrepreneurs, among them Bill Gates, report that one of the greatest rewards in starting a business has been to create jobs. All successful entrepreneurs will tell you that, had they passed by their opportunity to start a company, they would have regretted it for the rest of their lives.

Making money is seen by many as a questionable career goal, venal and self-serving. In the 1987 film “Wall Street,” Michael Douglas’ deal-making character Gordon Gekko famously says, “Greed, for lack of a better word, is good.” That snatch of film footage continues to resonate as a misleading portrayal of what constitutes “business.” Partly as a reaction, interest in “social entrepreneurship” has led to the formation of tens of thousands of not-for-profit organizations, many now referred to as non-government organizations or NGOs. Most of these organizations exist to provide what in the past would have been called a charitable service to people too poor to fully participate in the marketplace. Not surprisingly, failure rates for social entrepreneurs are very high.

Many entrepreneurs who have become part of a local ecosystem face a second distraction to their goal of making money. You are not starting a company to revive the local economy. Many colleges, especially in rustbelt cities, encourage entrepreneurship among their students as evidence of the institution’s commitment to helping its hometown. Similarly, many cities support business incubators in hopes that entrepreneurs who create businesses while working in them will add to the commercial base of the city. The job of getting a startup underway is hard enough without taking on the task of rekindling the economy around you. No entrepreneur should feel obligated to revive a local economy; her job is to get a business started that will attain scale growth and to maximize its likely success. What if achieving these milestones requires relocating to another city? Big businesses move to maximize efficiency; so should startups.

Sign Up: Receive the StartupNation newsletter!

If opportunity doesn’t knock, build your own door

Every successful entrepreneur can point to one or two lucky incidents that shaped his success. Formal business plans never mention luck, for good reason. No one can teach you how to maximize good luck or avoid a bad turn of events.

How do entrepreneurs get to be in the right place at the right time? Thomas Jefferson is alleged to have suggested an answer: “I am a great believer in luck and I find the harder I work the more I have of it.” For entrepreneurs, good luck is a return on three kinds of hard work. First, the ability to create an innovation relates to the breadth of facts at your command. The more you know, the more creatively you can think. Louis Pasteur’s observation about scientific discovery applies equally to entrepreneurs: “Fortune favors the prepared mind.”

Second, entrepreneurs, must be effective at building valuable social networks. The more encompassing their web of relationships, the more likely it will produce new opportunities and lead to new ideas, better employees, and more sales. An analog of this rule explains one feature of labor markets. Most people who get a job on the basis of word of mouth, not being recruited or applying for work, benefit from the referral not of a close friend but someone in a more remote second or third circle of acquaintances.

Third, good luck involves making opportunity from accidents. Everyday occurrences, a new twist on a product design, or a comment made by a customer on a sales call, may open an unexpected door. Entrepreneurs must make their own luck or, as the comedian Milton Berle once advised, “If opportunity doesn’t knock, build a door.”

Being familiar with these perspectives on what every entrepreneur should know will help you find more value in what follows. These lessons do not serve as a formula for success in which each operates as a critical ingredient. In all likelihood it will be only after the fact that you will recognize which were most important to your experience. Without such experience, however, these elements, considered together, may help you understand the task of becoming a successful entrepreneur—and whether what’s required of you seems authentic to your aspirations.

“Burn the Business Plan: What Great Entrepreneurs Really Do” is available now at fine booksellers and can be purchased via StartupNation.com.