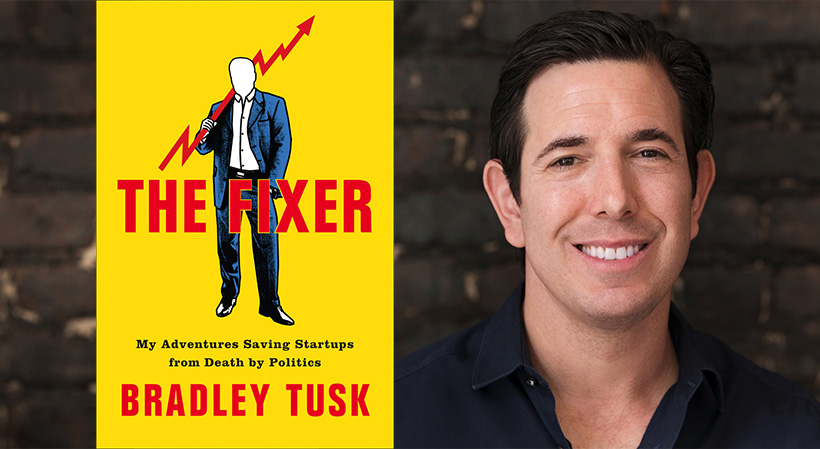

The following is excerpted from “The Fixer: My Adventures Saving Startups from Death by Politics” by Bradley Tusk with permission of Portfolio, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © Bradley Tusk, 2018.

“It’s gonna be huge,” the tech evangelists on my team argued.

“It’s never going to work,” the people who had worked in government and politics argued back.

I should have trusted Bob Greenlee and his team. They understood regulation. They understood politics. The people recommending MyTable to me understood neither. But I liked the concept and the success we were having was getting to my head, so I agreed—wrongly—to take them on.

MyTable was an L.A.-based startup that took the same concept that has made Uber and Airbnb so successful and tried to apply it to your kitchen. Just like people use their Toyota to make extra money by giving other people rides and people use their couch to make extra money by letting people pay to sleep on it, in this case, people would cook, post their offerings on the MyTable platform, and other people could buy it.

Imagine you live alone and you love lasagna. You can’t really make one serving of lasagna—you have to make a tray. To help cover the cost of the ingredients and your time, you can post, say, half the lasagna on the platform and sell it to someone else. (They can pick it up or have it delivered). MyTable’s business model was no different from Airbnb’s or any online marketplace—take a piece of the transaction each and every time.

Related: 5 Women Entrepreneurs Disrupting the Wine Industry

On the one hand, this made sense. Why shouldn’t people be able to monetize their kitchen? And while the idea of buying food from a stranger’s kitchen may seem crazy, how well do you know 99 percent of the restaurants you order from on Seamless? And is buying lasagna from a stranger that much weirder than getting in their car or sleeping on their couch? Platform businesses are attractive because you’re just connecting buyers and sellers, so the technology is fairly simple and the execution lies mainly in attracting people on both sides of the equation to the platform.

On the other hand, it made absolutely no sense. Departments of Health in every city, everywhere, inspect commercial kitchens. They make sure that food being sold to the public isn’t poisoned, isn’t contaminated, and isn’t made in a kitchen overrun by rodents. And while many government regulations are either the product of someone else just trying to stifle competition or a politician wanting attention, protecting public health and safety is probably the most legitimate reason for government to exist.

There’s no way health inspectors can start showing up in the kitchen of everyone who wants to sell their leftover lasagna to make sure the conditions are acceptable. I understood this going in, but thought we could develop a self-regulatory system to appease regulators: people would order their ingredients from a centralized, inspected location, we could livestream the preparation and cooking, we could have each seller sign an affidavit affirming they met a set of standards, and we could have a strict reporting system where any issues are quickly investigated by the platform. It was a major departure from the way things were currently done, but that’s the whole point of disruption.

MyTable was run by a smart, competent CEO named James Jerlecki, who understood that solving the inspection riddle was essential. James had managed to convince his six investors that the problem was solvable, and given how much some of my own employees loved the concept, it’s not hard to see how investors who weren’t that steeped in politics and regulation could look past the regulatory risk.

Not shockingly, soon after launching, MyTable was shut down by the health department in Austin, and then again in Los Angeles. We expected that. We made a list of cities that had tech-friendly mayors (and where we had good relationships; we did the same with states and tech-friendly governors) with the idea of piloting a self-regulatory framework there first, proving it worked, and using that to expand to other markets.

Sign Up: Receive the StartupNation newsletter!

We began with Providence and started talking to the city and the state. (There was some overlapping jurisdiction and Governor Gina Raimondo has a venture capital background, so if any politician understood the concept of looking at regulations differently to accommodate new technologies, she did). The challenge was that governments move slowly, and absent a jurisdiction agreeing to a framework with us, MyTable couldn’t operate and they couldn’t make money. James was running through his funding to keep the lights on, which meant he had limited time for something to happen. He couldn’t afford lobbyists, which we desperately needed to push the idea in multiple jurisdictions at the same time. There were a few other startups in the same space trying the same concept—Josephine, Umi Kitchen—but none of them wanted to work together, so we couldn’t even pool everyone’s resources. (Not every industry association works, but a number of our portfolio companies like FanDuel, Handy, and even Uber at times have been able to work with competitors to solve common regulatory problems even while still trying to kill each other in every other way).

Supporting a team of a dozen people is expensive (especially when you only raise under $2 million to begin with) and James ran out of money in about six months, long before we could get health officials in Providence to come around to a radically different approach to inspection and regulation. Without much fanfare, MyTable went bankrupt and we learned a valuable lesson—it’s fine to take on uphill battles, but if the resources to fight aren’t there, winning is unlikely. I should have known that going in.

“The Fixer: My Adventures Saving Startups from Death by Politics” is available now at fine booksellers and can be purchased via StartupNation.com.