In the early days of a startup’s journey, partnerships are often crucial. Teaming up with companies that have what you don’t yet—credibility and customers—can be one of the best ways to get your company on the map.

Later on in the journey, acquiring other companies—or being acquired yourself—is often the thing that we want to do to take our creations to the next level.

Trouble is, both of those things are extremely risky propositions. Working together with your own staff is hard enough. With all the potential that comes in a merger or partnership—or simply hiring people who bring something different to your table—comes also enormous risk.

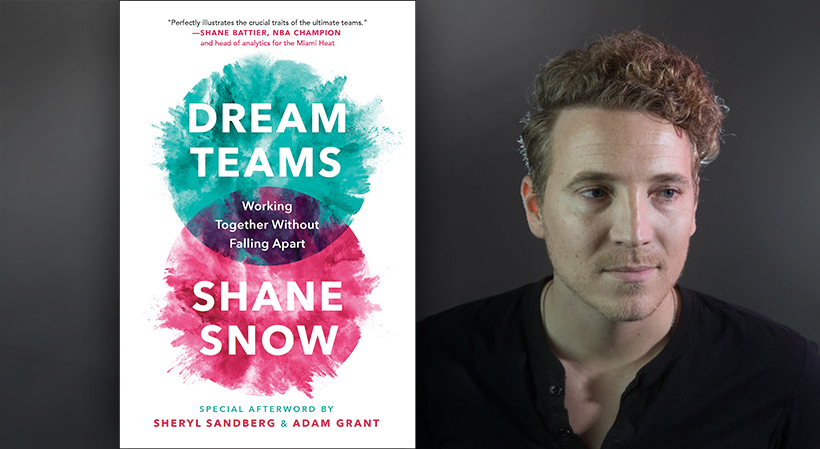

And the key to navigating those waters is not what we think. Here’s an excerpt from Chapter 2 of my new book, “Dream Teams: Working Together Without Falling Apart,” to explain.

The following is excerpted from “Dream Teams: Working Together Without Falling Apart” by Shane Snow, in agreement with Portfolio, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © Shane Snow, 2018.

According to the Harvard Business Review, between 70 and 90 percent of company mergers fail to achieve synergy. That is, they don’t manage to eventually turn two companies into one business that’s worth more than the sum of the individual companies’ value before the merger. More alarming, half of mergers actually result in a worse business.

Related: Tips for Successfully Leading Your Team Through Change

Few cases of this are as dramatic as DaimlerChrysler. Three years after the “merger of unprecedented strength,” the 100-billion-dollar company was worth somewhere between 44 and 48 billion—about what Daimler had been worth by itself.

It was supposed to be the greatest merger ever. A Dream Team of automakers. What happened?

The colossal failure has been the subject of many business school case studies. Some point to how the two companies overestimated their potential. Others illustrate how management stumbles hampered growth.

But those things alone didn’t wipe out 50 billion dollars in value. DaimlerChrysler didn’t crash because their cars got worse. Or because its managers forgot how to do their jobs. The cause of DaimlerChrysler’s epic tumble is the same thing that’s doomed the majority of mergers in modern business history.

The merger failed because of “cultural conflict.”

On the surface, Daimler’s and Chrysler’s people were very similar. They were four hundred thousand mostly male, mostly white engineers and designers and assembly-line workers and managers who loved cars.

“They look like us, they talk like us, they’re focused on the same things, and their command of English is impeccable,” said one Chrysler executive of his German counterparts, as reported in a Dartmouth case study. “There was definitely no culture clash.”

This assessment was laughably superficial.

The Germans and Americans who were now supposed to work together had different communication habits, different concepts of personal space, and different negotiation tactics. They had different core beliefs about women in the workplace and the role of leadership. They had different levels of intensity, different motivations, and different perspectives on what mattered when it came to making cars. In other words, they had significant diversity of perspectives and heuristics.

The new company spent a few million dollars on cultural workshops like “Sexual Harassment in the American Workplace” and “German Dining Etiquette.” But those were superficial, too.

From Daimler employees’ perspective, the goal of automaking was uncompromising beauty and precision. “Quality at all cost,” they would say. But to Chrysler workers, the goal was utility and affordability for their customers.

The Americans thought their new German coworkers were elitist. The Germans thought the Americans were risk takers with bad taste. Some Daimler executives even told the press that they “would never drive a Chrysler.”

Though their complexions were similar, DaimlerChrysler employees were as different as can be.

Sign Up: Receive the StartupNation newsletter!

Less than ten years later, the two companies broke up. Schrempp left amid shareholder anger. Eaton had been long gone by then. A private equity firm paid a reported $6 billion—10 percent of Chrysler’s 1998 value—to spin the Americans out. Soon after, that company went bankrupt.

Aside from the massive price tag attached, this is not a rare story in the business world. More than half of mergers lose value rather than maintain it. Half of those say the most significant factor in the failure was “organizational cultural differences.” Thirty-three percent say “cultural integration issues.”

In other words, most mergers that lose money don’t do so because of bad business. They lose money because their people can’t deal with their differences.

The key to navigating a partnership, merger, or ambitious recruiting strategy is not to be cautious with the tricky issues. It’s to make sure we address them candidly. It’s facing the friction head on! Read more at http://sha.ne/DT

“Dream Teams: Working Together Without Falling Apart” is available now at fine booksellers and can be purchased via StartupNation.com.