Living the lives of your customers and their influencers is a startup cheat code

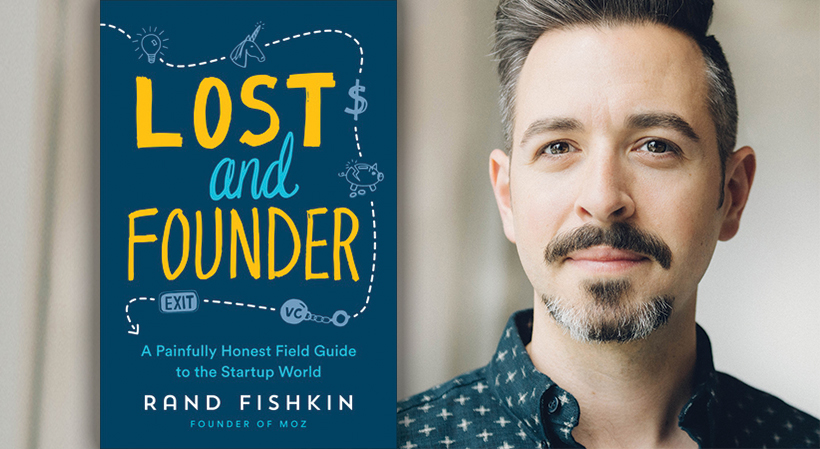

Excerpted from “Lost and Founder: A Painfully Honest Field Guide to the Startup World” by Rand Fishkin, in agreement with Portfolio, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © Rand Fishkin, 2018.

I thought I had an amazing idea. I thought it was going to change the world of marketing. I thought we were going to build a set of software that every business needed. I thought it would catapult Moz’s growth and revenues. I thought wrong.

It was 2011 when Adam Feldstein, then Moz’s chief product officer, and I sat down to plan out a project we called “Moz Analytics.” The new product stemmed from a theory I had that in the near future, the siloed practices of social media marketing, search engine optimization, content marketing, public relations, and online brand marketing would all merge into a single set of tactics undertaken by the same person or group at an organization. I saw how social media and content marketing worked together to bolster each other. I wrote and talked at conferences about how many PR and brand-building efforts were merging with SEO. I saw how a few organizations had already combined these practices into remarkable flywheels that generated returns greater than the sum of their parts. I knew these practitioners would need tools that worked together to optimize their efforts, track their progress and compare themselves against the competition.

Notice how I never thought to validate my idea externally? How nearly every sentence in the passage begins with “I”? You can almost picture the train wreck on the horizon.

Related: An Entrepreneur’s Basic Steps to Pay-Per-Click Marketing

Many paths exist to live the lives of your customers, but before you can do any of them, you need to know these people as people, not as “personas” or “sales targets.” I’ve found repeatedly that when our product and engineering teams comb through user interview or review data, we tend to create features and products that are barely better than the already-established processes our customers are using.

I think this happens because of how we’ve been socialized and trained to use data in professional environments. We see numbers, we analyze them and we make decisions based on how those numbers lean.

Say you’re tasked with making software to help people manage their finances. You survey a large group of people about their spending habits, what they want to track, what information they need to be informed about and where they have financial analysis pain today. The surveys and interviews reveal the ten most important categories of spending and that the proportion of spending over time and the absolute amount spent are both important. Thus, you create the same app that nearly every major bank and credit card has today to serve this purpose.

But if you knew the people personally, and spent time with them while they did their banking, financial management, and planning tasks, you might find that post-spending analysis isn’t nearly as important or helpful as alerts before they spend, tracking progress against goals, or incentivizing healthy spending and saving behavior.*

Facebook had a great example of this several years back. Internal data showed Facebook that many users loved to reminisce by viewing photos from years past. The high engagement rate these photos received prompted the social network to launch a new feature called “your year in review.” The feature was beloved by many, but also made headlines in the press because for some users who’d had tragic events, it was an unexpected, heartbreaking and painful experience. Eric Meyer famously wrote a blog post called “Inadvertent Algorithmic Cruelty” about the experience of losing his daughter, then seeing Facebook push photos and stories of her to him at unexpected times.

The data was clear, but empathy for the real-life experiences of a crucial subset of Facebook’s customers was missing. I want to believe that if an engineer on the Facebook year-in-review product had shared experiences like Eric’s, or if they’d known people who did, that feature would have launched with some preventative logic built in for those who’d experienced tragedy like his.

How do you get to an empathetic place for product design and development? Create regular customer exposure for your team and yourself.

That exposure can come through extreme efforts, or it can come from more subtle actions. There’s a few that have worked particularly well for Moz’s product folks and for other startups I’ve worked with, including:

- Conferences and Events: I get a lot of marketing value from speaking at events, but equally valuable is the exposure to professionals in our field who need and use the tools we offer. Hallway conversations, session Q&As, coffee meetings and after-hours hangouts offer a wide range of experiential cases from which you can gain perspective and insight. Just be sure to have a few consistent, open-ended questions that get to the core of your customer-empathy issues.

- Volunteering/Apprenticeships/Internships: A handful of startup founders and startup product owners have taken the innovative step of volunteering a day, a week, or even a few months through an apprentice/internship (formally or informally) with their customers in order to learn what their day-to-day work, challenges and current solutions look like. If you’re in the early stages and have the ability to be the customer you’re going to serve, even for a very limited period of time, I highly recommend it.

- Paid or Pro Bono Consulting: This is how Moz got its start. We were consultants first, built software that we ourselves needed, and then opened it up to a broader audience we’d built via our blog. Nowadays, I do this through pro bono consulting, and several of Moz’s other product contributors still do some independent paid consulting. It’s true that consulting doesn’t always provide perfect insight into the issues or work faced by your target customers (unless they, too, are consultants), but it can contribute experiences and build relationships you otherwise couldn’t get.

- Teaching: Not only does teaching require you to understand a subject or process deeply, it also gives you exposure to a wide range of practitioners or future practitioners of your subject matter. Those relationships bolster empathy as you show folks the what and how behind a process. It’s no surprise that so many professors and educators are recruited as startup advisers.

- Hiring or Contracting: If you or your current team have no bandwidth or no passion for embedding yourselves into your customer processes, there’s no shame in recruiting to help fill this gap. We’ve done this many times at Moz, hiring SEO professionals who know the field well and have used dozens of tools for years to assist us in building better software for customers like them. The key is identifying those individuals who can translate their own problems into more global solutions and have a product-driven mind-set, rather than focusing exclusively on their own processes. We’ve done best with this through the worlds of social media and blogging, ID’ing folks whose public contributions to the field clearly show an affinity for holistic, empathetic pattern matching and helping the industry as a whole.

Sign Up: Receive the StartupNation newsletter!

Thankfully, after learning from my mistakes with Moz Analytics, a couple of years later I was given a second chance to build a new product.

*Yes, I realize that these types of features might dissuade a person from spending as much, running counter to the financial institution’s goals of getting them to spend more (and hence won’t be popularized in their feature sets).

“Lost and Founder” is available now at fine booksellers and can be purchased via StartupNation.com.